UPDATED with more details on the unitary rotation vector representation of the test interaction (see section UPDATE below)

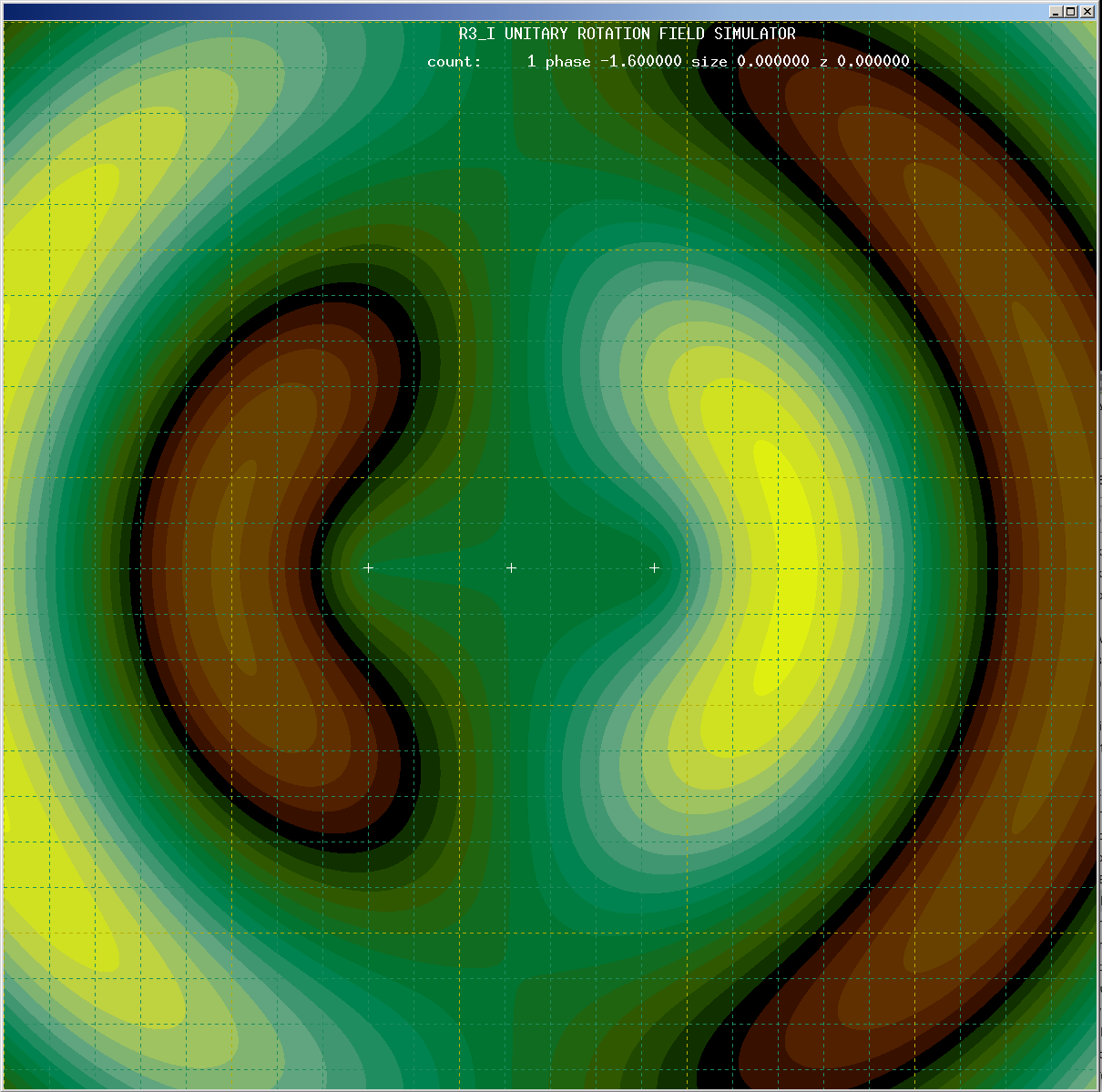

The latest simulations have shown some wonderfully interesting results. The last post showed how the Unitary Rotation Vector Field theory demonstrates particles that can both repel and attract due to quantum interference effects that relocate the stability region of particles. You can read about these results in previous posts, here is a schematic diagram of what happens, along with some sim output pictures demonstrating the principle:

I never intended to create a theory that competes with quantum field theory, but the principle of charge attraction and repulsion traditionally is derived directly from quantum field theory methods. So, it seems well worth the effort to compare the two approaches, and what I hope to gain by analyzing the properties of the unitary rotation vector field. While I have run unitary rotation vector field simulations of many particle types and interactions, I think it will be illustrative to compare how each theory handles the simplest interaction of a pair of electrons (charge repulsion).

Quantum field theory solves interactions like these by using LaGrangian mechanics, that is, minimizing the action scalar. Doing a path integral of the LaGrangian over all paths, and setting the the derivative of the action at all points over time to zero yields a motion equation for the particles in the system. This computation will find the path of minimum action and thus will correctly represent reality. More specifically, the interaction of the two electrons is mediated by virtual photons–particles that do not reside on the surface of valid position/momentum solutions in space and time (off mass shell). By prepending a creation operator to the photon wave equation and appending an annihilation operator after it, quantum field theory creates a solution where the time evolution of the electrons go in opposite directions (repulsion).

On the other hand, the unitary rotation vector field (nearly identical to a Pauli spin matrix representation) gets repulsion and attraction in a different way. Both theories do sums of wave paths to find regions of quantum interference, but the wave equation is different. In quantum field theory, the wave equation is the Hamiltonian–the sum of energies such as kinetic energy and the voltage potential in an electromagnetic field. The creation/annihilation operators are probability functions for emergence of virtual particles. The integral is computed over sufficient time so that an operator isn’t left stranded (virtual particles wont conserve momentum in that case).

The unitary rotation vector field is different–it is single valued with only one rotation possible at any given point, and this constrains where particles can exist (the stability region) because the particle phase and the wave phase must match (see the above schematic).

The wave equations in quantum field theory have wave solutions that propagate over time (for example, the propagator in the La Grange equation of action). Solutions depend on virtual particles that don’t obey classical physics. Quantum field theory can’t work without them because on-mass-shell particles will induce the momentum paradox described in the previous post. Nothing propagates in the unitary rotation vector field–each point just rotates, so conservation of momentum works without inducing the paradox.

Probably the biggest reason I pursue the unitary rotation vector field, rather than just sticking with the established science of quantum field theory? The rotation vector field seems to give another possible view of the underlying mechanics of particle interactions that might yield answers not covered by quantum field theory. The most significant possibility comes from how it postulates a formation of elementary particles from quantum interference in a field. There are other reasons, such as the theory doesn’t require renormalization methods, it doesn’t depend on off-mass-shell particles to work, and doesn’t have a probabilistic dependence on when virtual particles form.

Since quantum field computations work, it’s arguable my efforts are a waste of time (and certainly could be wrong, or not even wrong). But my curiosity is here, and so for now I will continue.

Agemoz

UPDATE: I need to clarify the Unitary Rotation Vector Field representation of the particles involved so you can see exactly how I set up the simulation. There may be other schemes that work, but this is the approach I used in my simulations.

The unitary rotation vector field is continuous and only rotates a unitary vector (like the Pauli spin matrix). It can point in any of the three real dimensions in R3 or in one imaginary direction (the background state of the theory). This is the same vector space as the continuous quantum oscillator field, except that there is no variation in magnitude and you cannot have a zero length rotation vector.

Being single valued, a rotation cannot pass thru from one location to another without affecting each location in the path. As a result, particles must have the same phase as the sum of wave rotations (that is, quantum interference computed as a path integral) at each particle’s location, this is called the particle’s stability region, shown in black on my simulation images. A particle cannot exist anywhere except in a stability region, otherwise the location would have to simultaneously have two different rotations. Particles are forced to move when the stability region moves–a well tested example is quantum interference resulting from a single particle passing through two slits.

Each field location can be represented by a set of three rotation values–one straightforward basis is a rotation set that resides in the plane that includes the I dimension and the X direction, a rotation that includes both the X and Y directions, and finally one rotation that includes both the X and Z directions. My simulation uses this basis. All rotations are modulo 2*Pi (the simulation values go from -Pi to +Pi).

A photon in this theory is modelled with a single quantized vector rotation from the +I direction thru -I and then continues to +I (see the image figure below). There is a lowest energy state at +I and -I, so once the rotation does one rotation, it stops. The photon also has a translation along some real dimension axis.

In the interaction of a photon and electron shown in the above simulation pictures, the photon induces either a positive or negative rotation offset to the receiving electron, which causes the electron stability region (via quantum interference) to displace either above or below (attraction or repulsion respectively). The photon must be able to carry a positive or negative momentum. You can see that the rotation must lie in the plane that includes both the +I and the translation direction vector (otherwise you will not have photon polarization using any other rotation scheme). Note that there are two possible rotation directions–either rotation begins moving toward the direction of travel, or away from it, corresponding to the two possible rotation offset directions intercepted by the electron.

The really interesting thing about this configuration is that the photon becomes a momentum carrier, but intrinsically does not have any actual momentum due to its translation. The source particle emitted momentum is carried by the photon’s rotation but the photon has no momentum of its own (consistent with the fact that photons are massless particles). This is what allows photons to pass along either negative or positive momentum without inducing the momentum paradox. That is, shooting a massive particle at a destination particle cannot ever cause attraction, but photons can.

This seems to be a much better scheme for how photons carry electrostatic force than the virtual particle scheme used in quantum field theory. Virtual particles are just assumed to not obey momentum/position conservation from creation to annihilation, which means I can’t simulate it. I can only define the interaction as a black box. It computationally works, (there’s no way ever that I would say quantum field theory is wrong!!!) but my goal is that the unitary rotation vector approach could lead to a deeper understanding of particle interactions.

Agemoz

Tags: interference, physics, quantum, quantum field theory, simulation

Leave a comment