Every physics student knows that quantum physics interactions are computed using wave functions as probability distributions. Rather than computing time evolving waves, we compute time evolving probability distributions, which has led to the conclusion that probability is an intrinsic property of elementary particles. We are taught to avoid applying classical mechanics to quantum events, but Einstein struggled with this conclusion and made the famous claim that “God does not play dice”. As I mentioned in the last post, there’s a simple explanation for why we cannot observe deterministic time evolving of waves and particles–waves result from zero time oscillations.

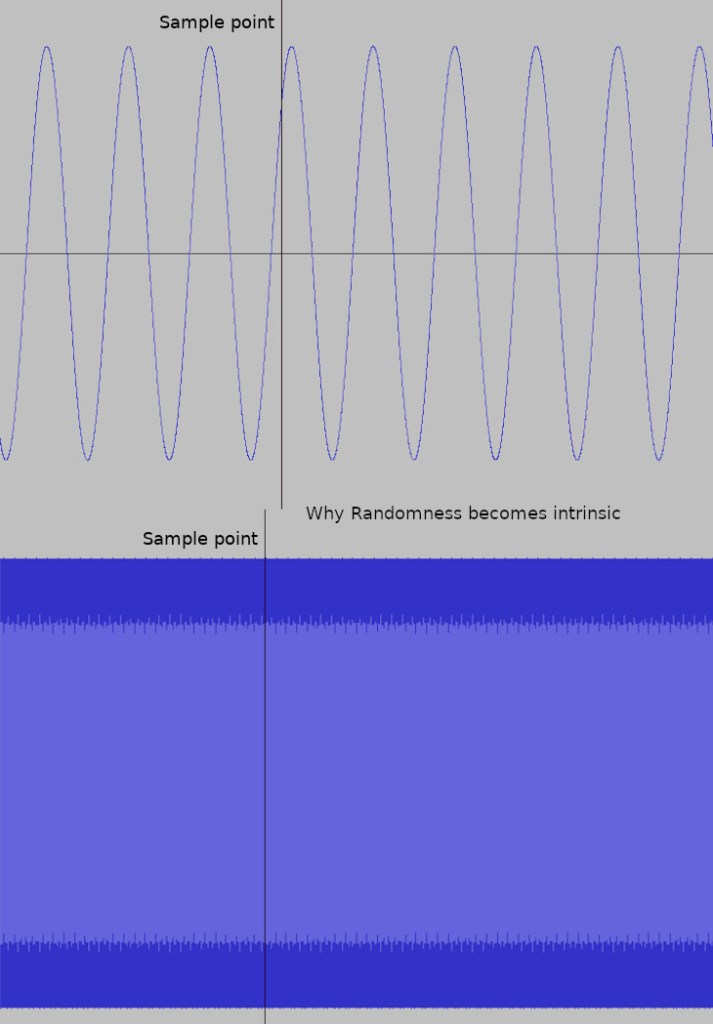

I think that a faulty assumption could have been made here (that quantum particles have an intrinsic random property). Every quantum experiment we can do shows the probabilistic nature of wave interference–but that doesn’t necessarily mean that we can never apply classical mechanics principles and laws (“shut up and calculate”). What these experiments really show is that we as observers cannot observe anything but a probability that something will have a given outcome. This can happen if particles have truly intrinsic randomness, or, it can mean that the rotation of a particle state takes epsilon or zero time and we can’t determine the phase of a rotation at any given point in time. Our instruments require a time interval and can’t catch a zero time wave phase. I think we have to choose one of those two assumptions, it’s not necessarily the case that randomness is truly intrinsic to quantum interactions.

To me, another part of established science confirms the idea of zero rotation time: the magnetic moment of an electron. As I described in a previous post, a inertial moment of an object is the integral sum of all point elements (such as a delta mass or charge) times its radius from a rotation axis, times the frequency of rotation. For a point particle, the angular moment results from a zero radius, and thus requires an infinite rotation frequency (zero rotation time) to get a finite inertial moment that appears when a magnetic field is applied to an electron. Just like the wavefunction probability distributions of quantum theory, this supports the idea of zero-time rotations.

So, I looked at this more, and combined it with the idea that particles are quantized unitary rotations, or vector twists, in 3D+T dimensions, where the T dimension direction is a background state. In previous posts I show that it is not possible to do a twist rotation in 3D without incurring a field discontinuity, but it is possible in four dimensions.

Now, if rotations occur in zero time, how do we get the non-zero wave time of the electron’s quantum interference property? A rotation of a vector that takes 0 time forms a disk, but we need to be mindful of the zero point size and zero rotation time, so this disk could be treated as an epsilon size and time while applying another classical property, precession. If the disk rotation plane (of epsilon size) does not line up with the inertial moment plane normal to its axis, the disk will precess at a rotation rate inversely proportional to its mass. I think this is where the quantum interference wavelength comes from. From previous posts, you can see that the elementary particle twist rotation occurs in the 3D+T plane that lies in one of the R3 dimensions and the T dimension direction (because this quantizes the rotation, see many previous posts). However, the particle’s magnetic moment lies in either the other two dimensions of R3, or in one of the other dimensions of R3 and the T direction. This particle of epsilon size and epsilon rotation time will precess in the plane normal to both the twist plane and the inertial plane. In this approach, photons are similar but the twist lies in the plane formed by one of the R3 directions along with the T dimension direction. Polarization is a degree of freedom set in the other two R3 dimension directions. Photons do not have the zero-time rotation and thus do not precess.

Now we can look at what happens when an electron and a positron collide to form two photons. It is established science that the collision removes the mass and charge of the incoming particles, and redirects the photon paths to lie on the lightcone (mass and kinetic energy is converted to frequency). If e- and p+ are precessing twists, note that the base frequency of the twist has to remain. You don’t have to assume twist theory to know that the photon energy frequency and the quantum interference frequency of the electron and positron are the same if there is epsilon-zero kinetic energy. The only thing that is cancelled out is the zero time twist! Therefore, both charge and rest mass then would have to be due only to the zero-time twist behavior of the elementary particles e- and p+. The photons have neither, so the precession of the zero-time twist becomes a non-zero time twist in the same R3+T plane but now moving on the lightcone.

Is this reality? Dunno, but it’s definitely a different way of thinking how quantum particles interact that doesn’t require intrinsic randomness.

Agemoz

Tags: general relativity, general-relativity, physics, quantum, quantum theory, special relativity, special-relativity

Leave a comment