In my last post, I showed why there is reasonable evidence that elementary point particles have simultaneous spins on two axes. I have found that in our 4 dimensional (R3 +T) existence, point particles are really interesting entities, and lead to several ideas such as why we have a set of 4 electron class particles with the same charge magnitude and mass. Further study also shows that such particles have one of the spins quantized, leading to a hypothesis why we have elementary particles of specific mass and charge.

The analysis of the electron-positron collision into two photons led me to this dual-spin idea. There are other experimental results that also point to this, but this one in particular shows how a spin-based model of elementary particles must consist of spins on two normal axes. This assumes that photons are spins lying in the R1-T (the x and time) dimension subplane of our 4D existence, and that elementary (massive) particles have that spin but also have a spin in the R2-R3 (that is, the y,z) dimension plane. When the electron and positron (or any other complementary particle pairs) collide, the R1-T spin remains as photons, but the R2-R3 spins cancel and vanish. The charge properties of the colliding particles also vanish, strongly implying that charge is a result of the R2-R3 spin.

This motivated me to dig deeper, so I applied some study time to the concept of dual-spin elementary point particles, and came up with two charming surprises.

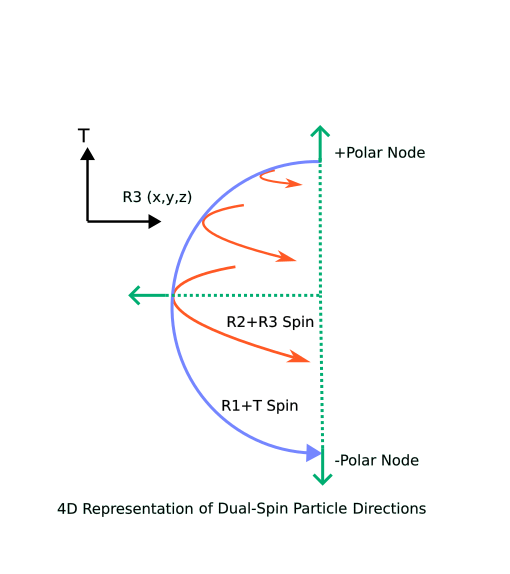

We all know that spin (rotation, twists are all analogous words in this study) is a direction vector property where the vector rotates about an origin point, and that any spin that has no angular force applied to it will lie in a 2D plane. We can have a vector spin in 2D space, but in 3D, vectors can still only spin in a 2D subplane. However, in 4D, such as our R3+T existance, it is possible for a vector to spin on two axes at the same time. It is tempting to think that these spins are independent, but they are not. There is only one vector, so at the poles of one spin, the other spin has a node where its position must be defined and the spin itself is undefined.

Quantum mechanics deals in wave functions of spin, and the component probability amplitudes must line up at node points. In atomic orbitals, this requirement quantizes the available orbitals–similarly, dual-spin particles are quantized at the poles (the +T and -T spherical orientations, for example). To clarify, the first spin (R1+T) sets node points for the wavefunction of the second spin (R2-R3). The second spin wavefunction must be an integer multiple frequency of the first spin in order for its node points to be identical to the first spin orientation.

This is very interesting to me! First, note that there are four electron class particles, the spin-up electron, the spin-down electron, the spin-up positron, and the spin-down positron. The dual-spin point particle concept gives rise to exactly 4 unique cases and thus is an exact match for describing the four electron class particles. I have to be careful here, because we have to ensure that any pair of these cases are unique even from a rotated observer’s point of view. You can prove this if you set an observer frame of reference on the first spin rotation. The first spin’s crossproduct can be either positive or negative–giving two spin states relative to the +T direction. For each of these, in that spin’s frame of reference, the crossproduct of the second spin then has either a positive or negative value, thus giving two unique states for each of the two original spin states. They do not overlap and give four unique spin states.

Second, and much more interesting, is that with this quantized second spin, I see good reason why we see quantized versions (for example, of charge and mass) of the various elementary particles. For example, the electron class particles should have an integer multiplier of 1:1 with the first spin cycle, and quarks have an integer multiplier of 1:3–but since charge must result from the second spin cycle rate (refer to the electron-positron collision where charge has to come from the second spin), it must be a rational fraction of the charge of the electron. What about 1:2 or other multiples, and what binds the quarks? We can stick with quantum field theory to do this, but I want to pursue this to see if there might be more to discover.

UPDATE: we can only get odd multiples, the 1:2 case is not possible. The 1:2 gives a direction that won’t line up with -T at the bottom “south” pole. Therefore, a particle with 1/2 charge is not possible.

Dual-spin point particles in R3+T are fascinating entities that I think have a lot of potential for interesting study.

Agemoz

Tags: general relativity, general-relativity, physics, quantum, special relativity, special-relativity

Leave a comment