In the last post, I stated that if an electron were truly an infinitely small point, and electrostatic fields obeyed the central force relation where force decreases with the square of distance, we should see electrons able to achieve very high velocities. There is an analogy with gravitationally driven masses that slingshot around other masses and gain sufficient momentum to exit the solar system. For example, the P orbital (second excitation state of electrons in an atom) has a probability distribution that intersects with the nucleus, so close encounters should cause large central force acceleration such that the electron would be ejected from the atom at high velocity. We never see this happen for stable atoms, so I concluded that one or more of our assumptions has to be wrong. Either the electron is not a point, or electrostatic fields do not follow the 1/r^2 decrease in strength away from a charge source.

I think enough experiments have been done to show that the bare electron has to be a point as far as we are able to measure. I think trying to find a solution that depends on a significant electron radius is a lost cause.

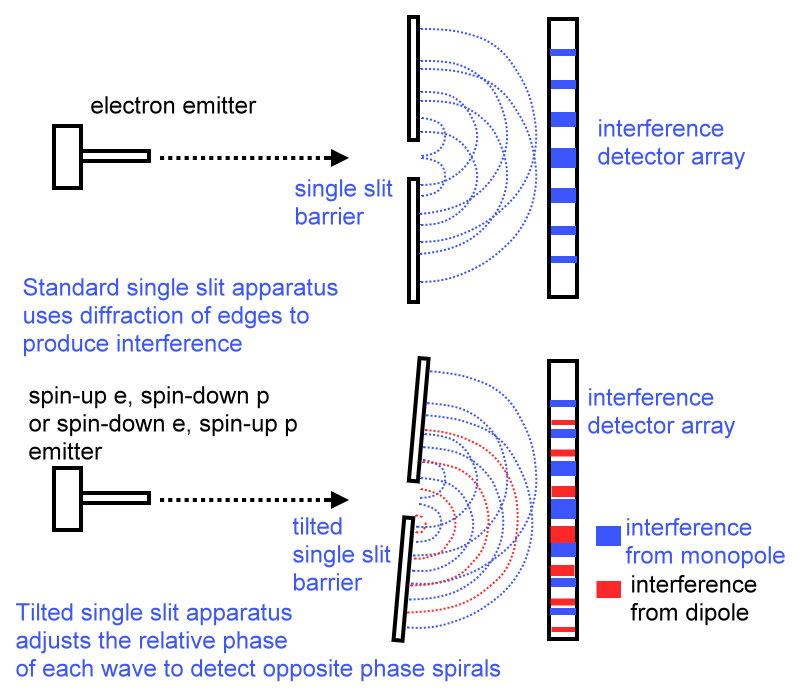

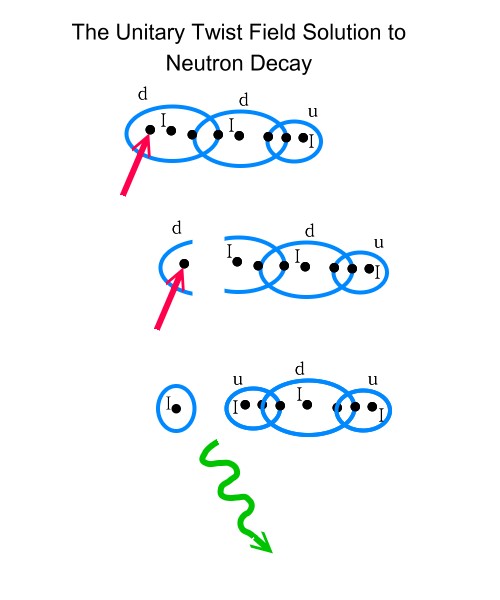

However, I have posted many times working out ideas how the electrostatic field has to be exerted via sinusoidal waves. We already see wave behavior from quantum particle experiments, so I ran several simulations that showed how charged particles are displaced, either as attraction or repulsion, via quantum interference–waves summing to form interference patterns defining particle location probability bands. This led to the hypothesis that charge forces are a consequence of quantum interference, and that the electromagnetic field consists of waves.

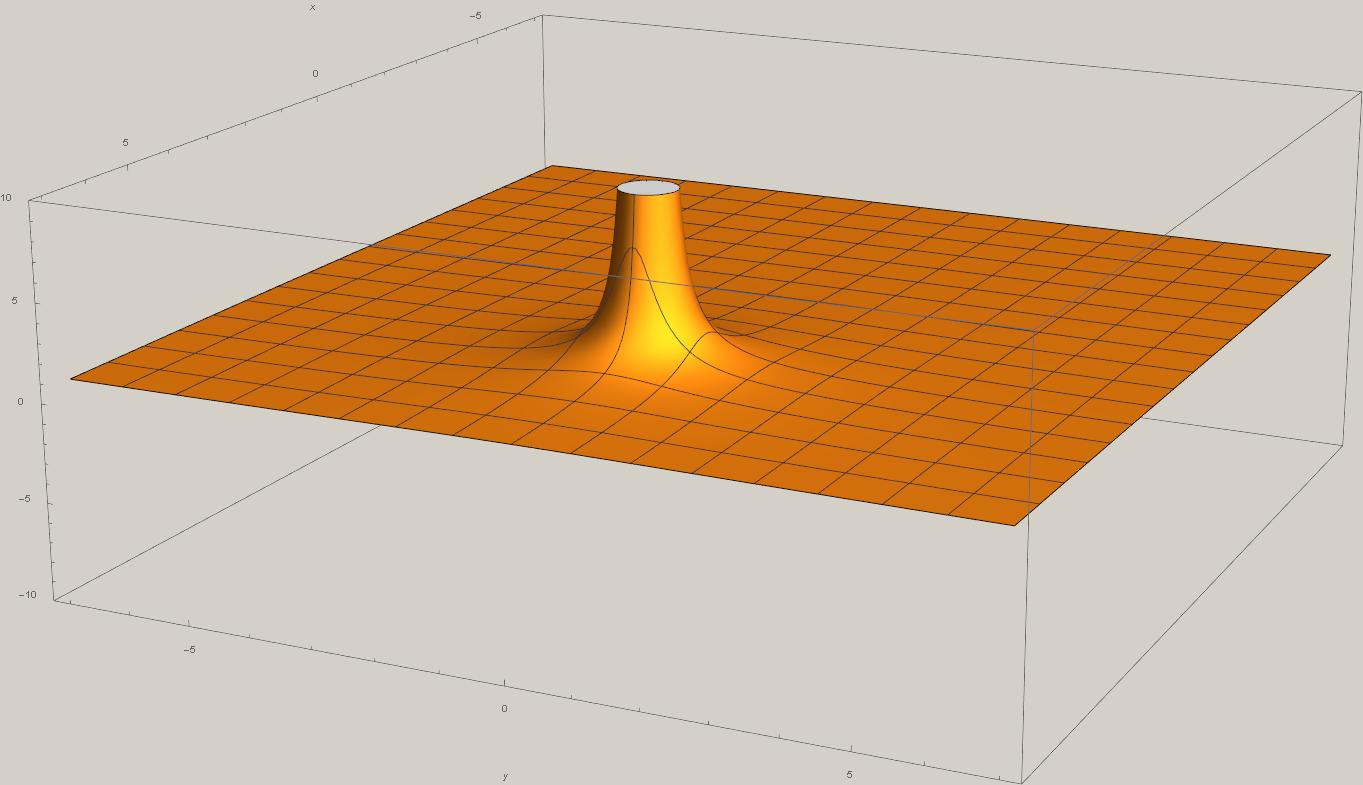

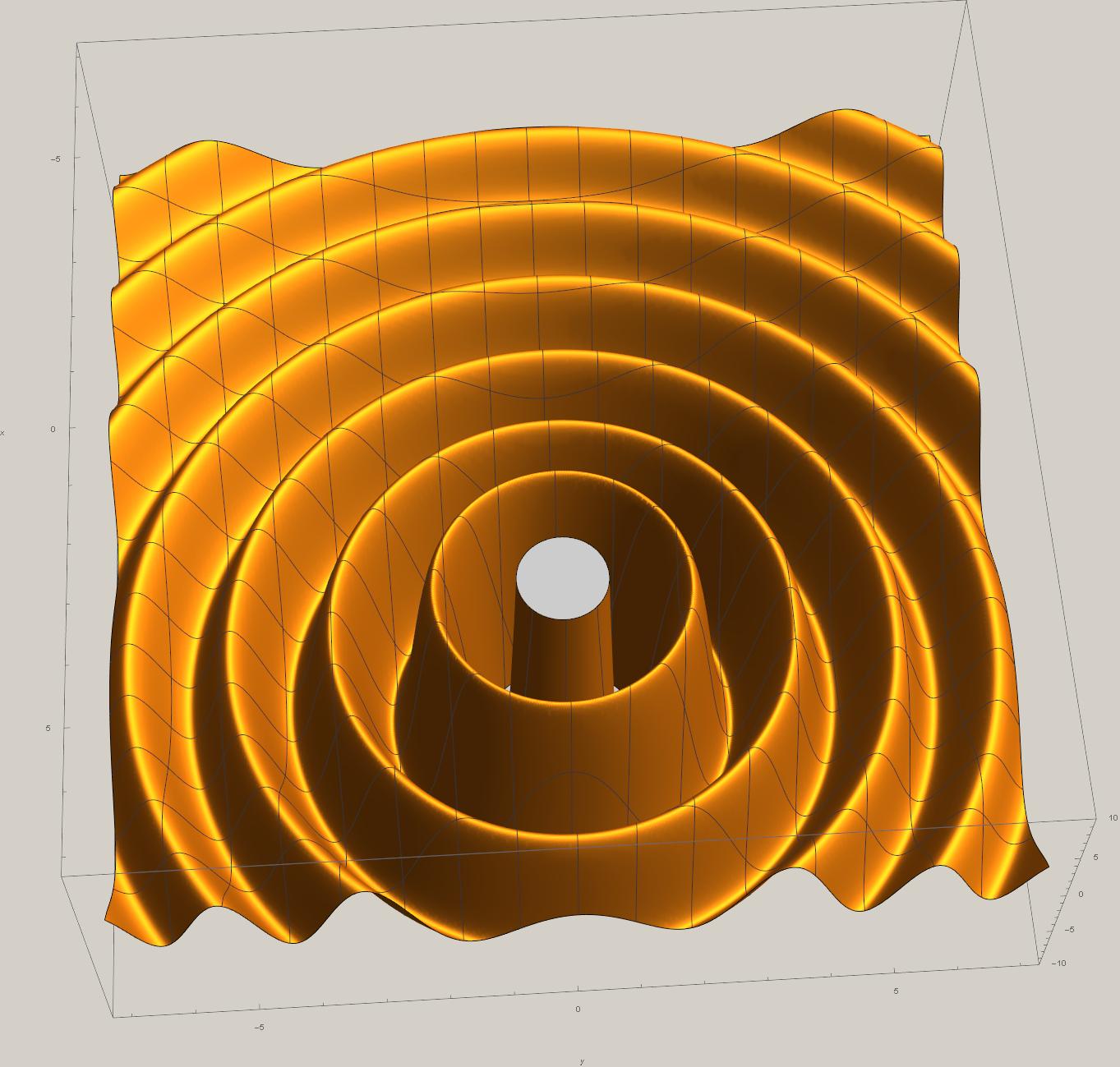

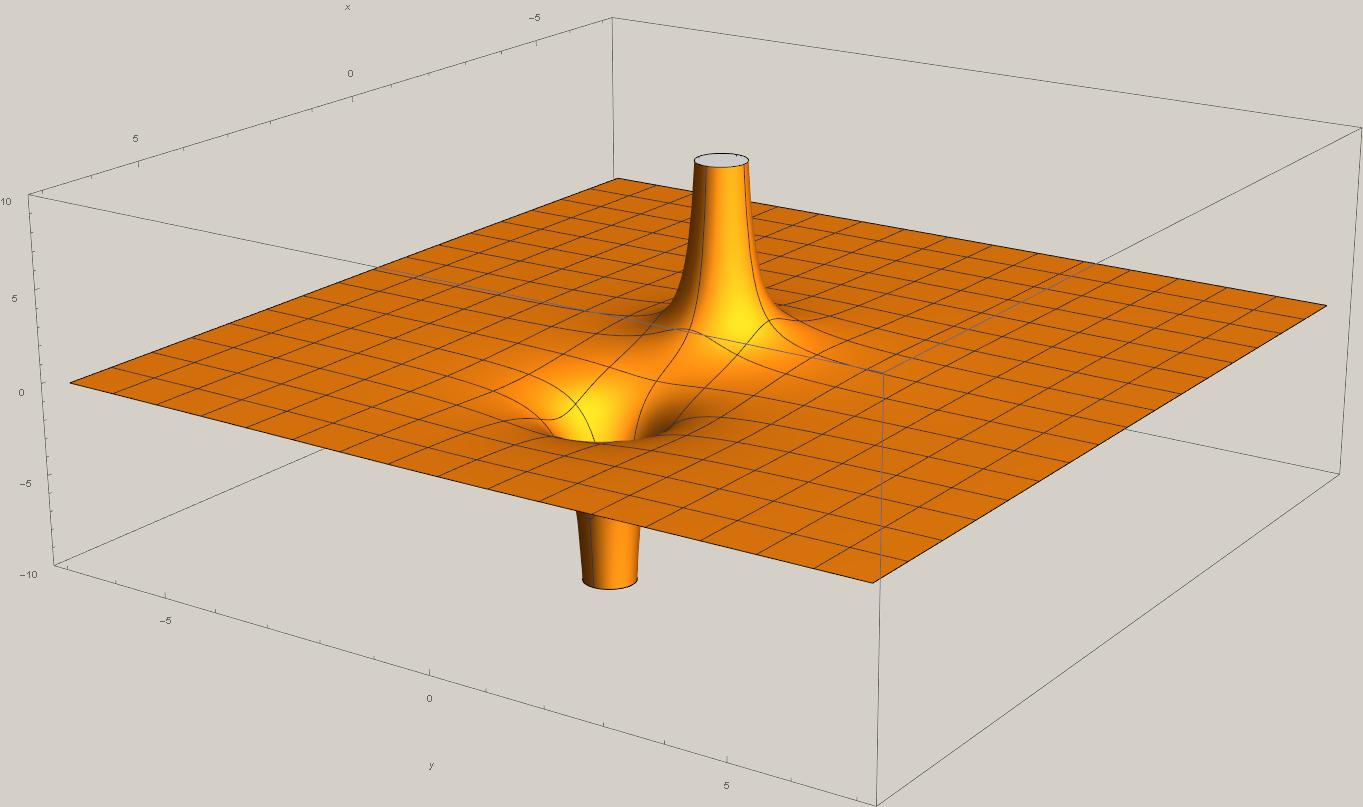

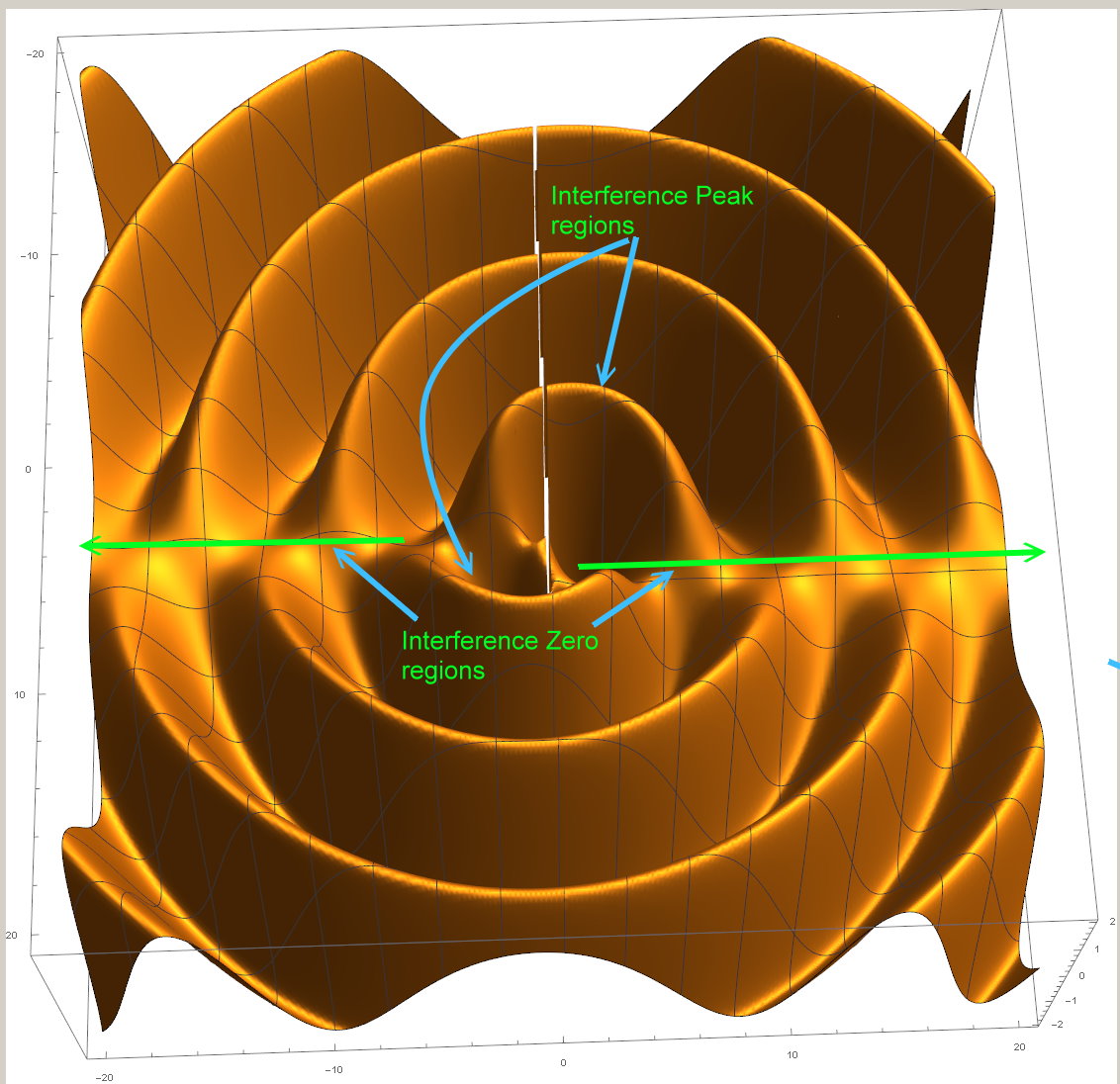

Recently I’ve been questioning why quantum field theory has to use renormalization to cancel out infinities caused by the central force behavior of electrostatic fields. This (and the gravitational mass analogy positing spontaneous expulsion of electrons from atoms) has led me to think that modelling the field as a 1/r^2 central force field is incorrect. I conclude that the electrostatic field near a point charge has to be represented by a probability amplitude, not of 1/r (which would yield a probability distribution of 1/r^2), but must also include its wavelike nature. This means that the probability amplitude would be a sync function: Sin[r]/r, giving a probability distribution of Sin^2[r]/r^2. Now we should not need to renormalize, and we also would no longer have the possibility of electron expulsion from an atom. We still retain quantum properties such as the wavelike interference behavior of particles, but will no longer have infinities caused by a pure central force field.

Agemoz