UPDATE: chart of all possible dual-spin combinations, both unquantized and quantized.

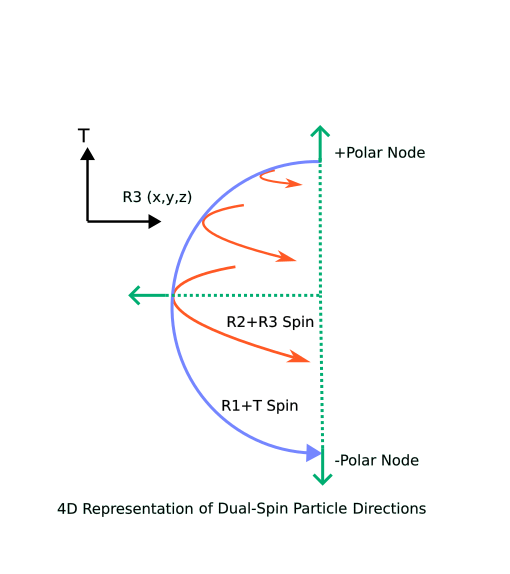

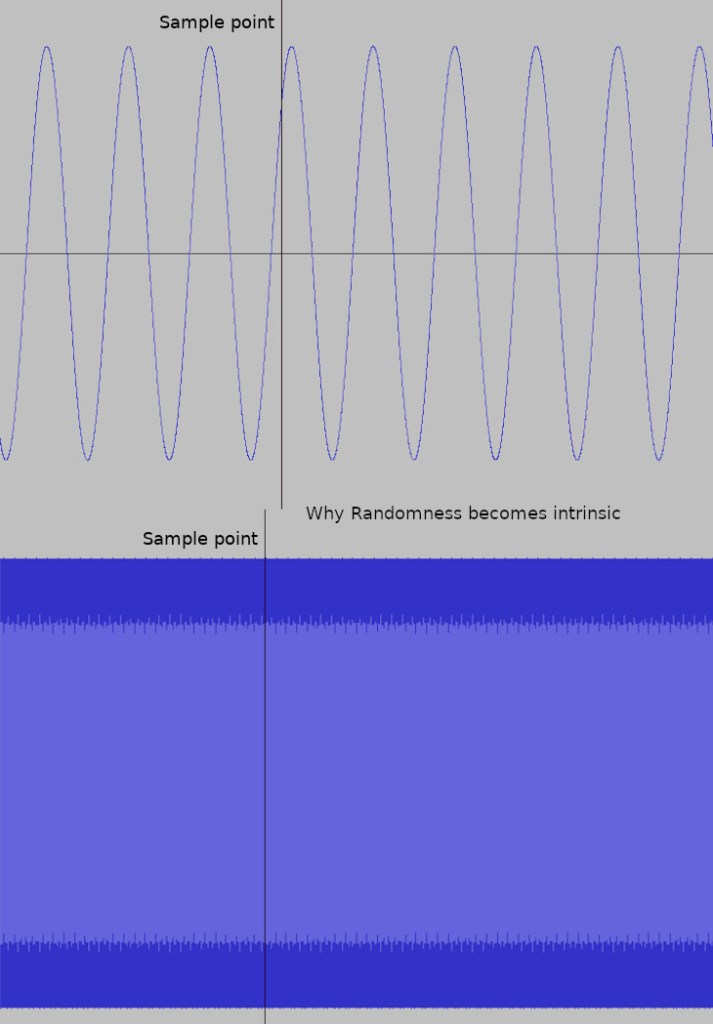

In our four dimensions (three space and one time), a single point particle can have two independent spins within two orthogonal planes, such as the plane lying in R1+R2 and another lying in R3+T. This fact, coupled the fact that our existence and interactions are confined to a R3 hypersurface “activation layer” within the R3+T universe, gives point particles a lot of interesting properties that point to why we have the particle zoo in real life, see https://wordpress.com/post/agemozphysics.com/1784. The most important property is the ratio of the two spin rates–when these are described as spin wave functions, we get quantization of the probability distributions. When combined with the activation layer, a single R3+T dual spin particle will pop in and out of existence, and it will appear to observers as multiple pseudo particles.

This system gives us the necessary degrees of freedom to specify charge and the different particle types such as the four electron-class particles (spin-up electron, spin-down electron, and their positron anti-particles). When the spin ratio has a factor of three, we get the degrees of freedom necessary for color charges and electric charges of several quarks, including the excited quark combinations of the various Delta particles. Even the particle masses due to the binding energy of quarks have a workable mechanism because force on particles is dependent on the percentage of time the particle spends in the activation layer. The higher the dual spin ratio, the less time external forces can affect each pseudo particle, and thus the higher the apparent mass of the particles.

One really nice thing about dual-spin point particles is that being a point particle, it is immune to concerns about relativistic invariance–with no time or spatial distance in the particle definition, the metric is always zero. All the properties I discovered so far do not have any danger of violating relativity.

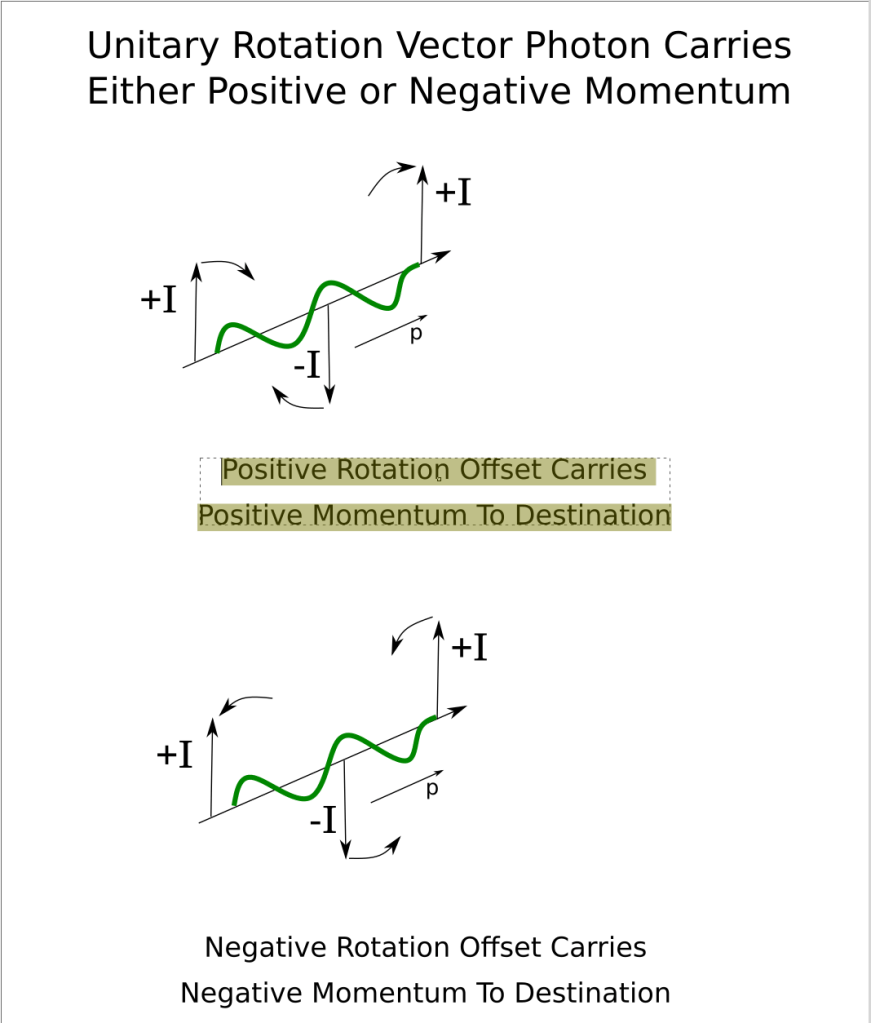

One of the strongest reasons I think these dual-spin point particles match reality comes from the known behavior of half-spin particles. I was fortunate to attend one of Professor Feynman’s last lectures before he died, and I remember him discussing that half-spin particles do not have classical spin, but require two complete revolutions before returning to the original state. He used his hands to model how one quantum twist rotated the spin axis normal to the spin direction, and that two twists were required to return to the starting position of his hands. If ever there was a clearer example of the multiple dimensional nature of quantum particle spin, I haven’t seen it!

All of these R3+T point particle properties seemed to work fairly well matching the necessary degrees of freedom present in the Standard Model until I started evaluating the Higgs field. There are a lot of questions still, such as how we get the strong force/electric force counterbalancing within a nucleon or particle decay times, but nothing has really shut things down as much as trying to integrate the Higgs field into the dual-spin point particle idea.

The Higgs field, which is a constant scalar field regardless of the chosen frame of reference or the presence or absence of neighborhood particles, applies a drag to the motion of particles and is responsible for the apparent inertial mass of the particles. There are some relativistic invariance problems here–first, the Higgs force only emits a Higgs boson to resist motion when the particle accelerates in some way, not when it is moving at a constant velocity. Thus calling it “drag” is not a good label, it only “drags” changes in motion–how does the field know the difference? And secondly, there is no Higgs boson emission when observed in the frame of reference of the accelerating particle, so the field itself must be accelerating in that case–and then you really run into relativistic invariance problems because Higgs bosons are massive, and you just caused the mass to disappear!

The Higgs field is really treading dangerous ground given that the luminiferous ether was proven not to exist (see the Michelson-Morley experiment). A model having a constant scalar field which applies drag to particles sounds a lot like something that would break relativistic invariance no matter what mathematical hijinks are done.

Something feels off here in my understanding, and until I get past that, I won’t have a way to match the Standard Model mass effect. I like to think that the dual-spin point particle idea doesn’t need the Higgs field, but that fails when trying to understand why scientists have already detected the Higgs boson.

Agemoz