Edit: Looking at the LaGrangian (equation of motion) for the strong force, which has been developed and refined over decades, I kind of noped out on the dual-spin idea for quark/gluon interactions. I did get a good sense of what chromodynamic color is–it’s not a property of quarks or gluons, but a mathematical device that ensures which particles can interact with each other. One way to determine this is the fact that all color quarks interfere, and all color pair gluons interfere. I thought the coupling number tensor field adds a crazy degree of complexity that something simple like the 4D dual-spin point concept cannot begin to cover. It’s worth it to study the LaGrangian and SU(3) in more detail, but all this really does throw a monkey-wrench in the works for dual-spin point particles.

Edit #2: Added note that shows that the 4D dual-spin point particle concept not only shows a clean explanation (conversion of angular to linear momentum) for annihilation products of electron or quark particle/antiparticle collisions, but it also shows why those are the only direct products of the collision.

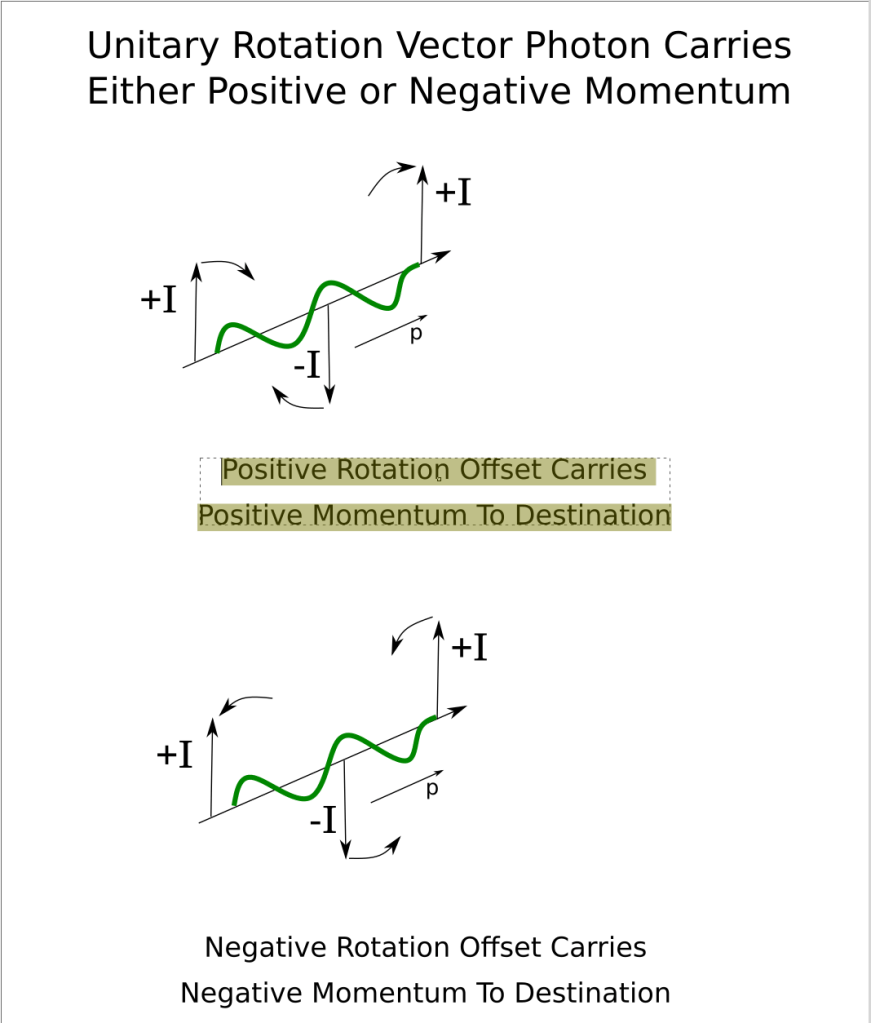

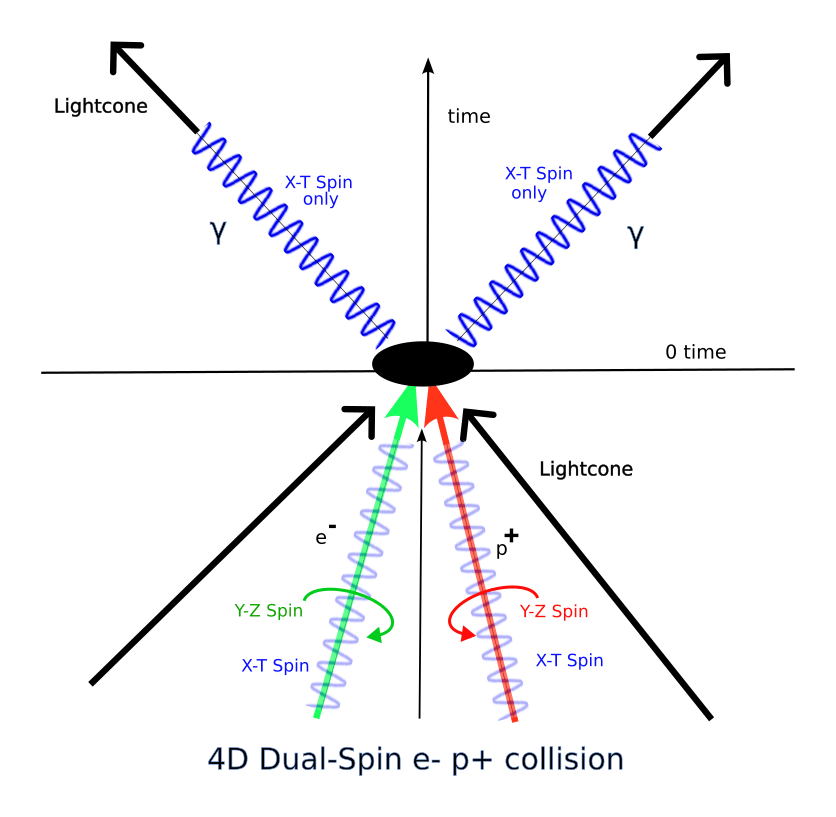

In the last post (https://agemozphysics.com/2024/05/12/spin-wave-functions-in-the-e-p-dual-spin-annihilation/), I showed how the analysis of 4D dual-spin point particle/anti-particle annihilation gives an elegant picture where annihilation is the process where one of the dual spins’ angular momentum components gets converted to the linear momentum of, for example, the resulting photons. This analysis then shows how to derive the quantized angular momentum /h (reduced Planck’s constant) of the source particles.

While this derivation was shown for the electron/positron annihilation case, there is nothing in the formula that limits to the electron/positron annihilation case. In fact, some beautiful results occur when you apply the same work to quarks. Unfortunately, there is a rather stinky fly in the ointment to this line of thinking.

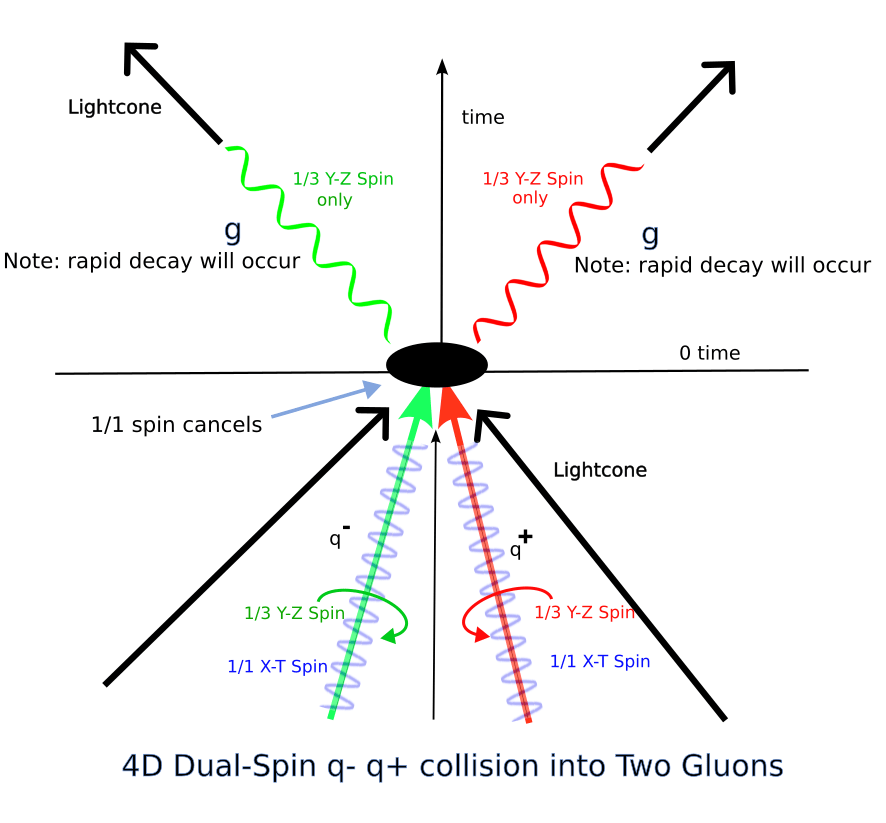

Unlike lepton/antilepton annihilation, which can only annihilate to two photons, quarks can annihilate directly to either a pair of photons or a pair of gluons. Like photons, gluons have a transverse polarization angle, and like photons, they have no rest mass and thus move on the lightcone at the speed of light. Quarks have charge magnitude of either 1/3 or 2/3, and in the dual-spin point particle representation, this means that one of the two spins has a 1/3 ratio to the other.

The beautiful thing about this representation is that in quark annihilation, you can annihilate (convert to linear momentum) either the 1/3 spin, giving a photon pair result, or the 1 spin, giving a gluon pair result. Thus, the 4D dual spin point particle concept makes a case for covering all three annihilation cases, the lepton and both of two quark particle/antiparticle annihilation cases. Since the lepton case only involves 1/1 ratios, you never get a 1/3 spin result and hence never see annihilation into two gluons.

Edit: Note that a quark-antiquark annihilation has no other direct result products–all other collision products require intermediate particles within the collision neighborhood. That is a nice affirmation of the validity of the 4D dual-spin point particle concept–it not only shows an elegant and simple way to get the observed collision products for both electron and quark annihilation, but it also shows why those are the only results.

Unfortunately, the quark situation is actually not this simple–this does not show why we have chromodynamic color constraints on quark interactions.

In the Standard Model, we represent reality by two overlapping fields, the electromagnetic field covered by U(1), and the strong force field, covered by SU(3). The strong force field can be represented by a unitary constrained 8 dimensional real-valued adjoint (diagonally antisymmetric) matrix with eight orthogonal eigenvectors. The EM and strong force fields are clearly not completely independent, or else we could not have particles that stay in the same place on both fields when either electromagnetic or strong forces are applied. As a consequence, unification of the EM and strong force fields seems to imply there should be a single field representation, and with these annihilation analysis results, I had thought the 4D dual spin point particle concept would get us there.

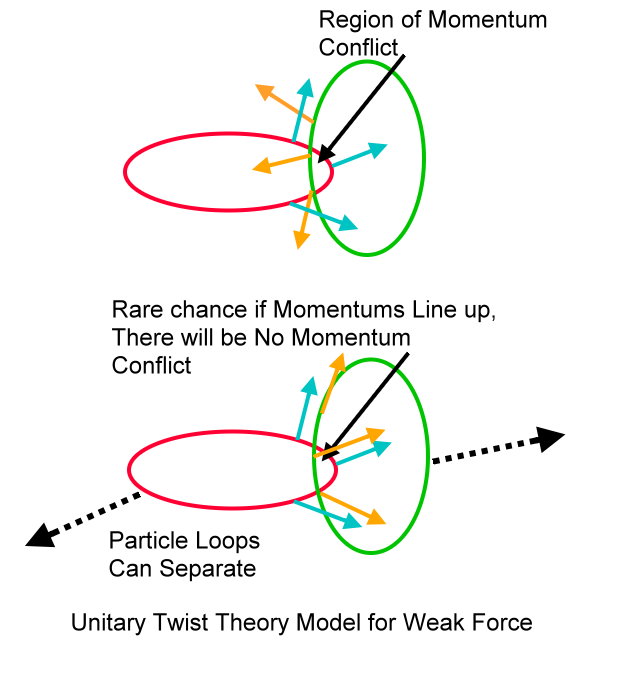

However, I currently see no way that the 4 dimensional dual-spin point particle representation could be sufficient to constrain chromodynamic quark/gluon interaction characteristics. I’ve studied this for a while and think something has to be added to make the 4D dual-spin point particle concept fully work for quarks and gluons.

In summary, I do think that the four-dimensional dual-spin vector field is a good starting point for unifying the electromagnetic and strong forces–it certainly seems to provide an elegant view of several fermion/antifermion annihilations and pointing to how to get the quantized moments–but as is, it is not sufficient to cover quark/gluon chromodynamic color constraints.

Agemoz