In my last post, I described how quantum field theories use perturbative methods to evaluate particle interactions, and posited that a better way will come from using the emergent field concept. Emergent fields are a type of field that has the creation/annihilation operator properties built in, and in the last post I began to describe what such a field would look like as well as the impact it would have on existing thinking about the standard model. This immediately opened a line of thinking where I think I see a better way to construct quantum field theories that doesn’t depend on particles. I still question whether this is right–but it seems to work, it is consistent with existing physics, and I think this might be a step forward.

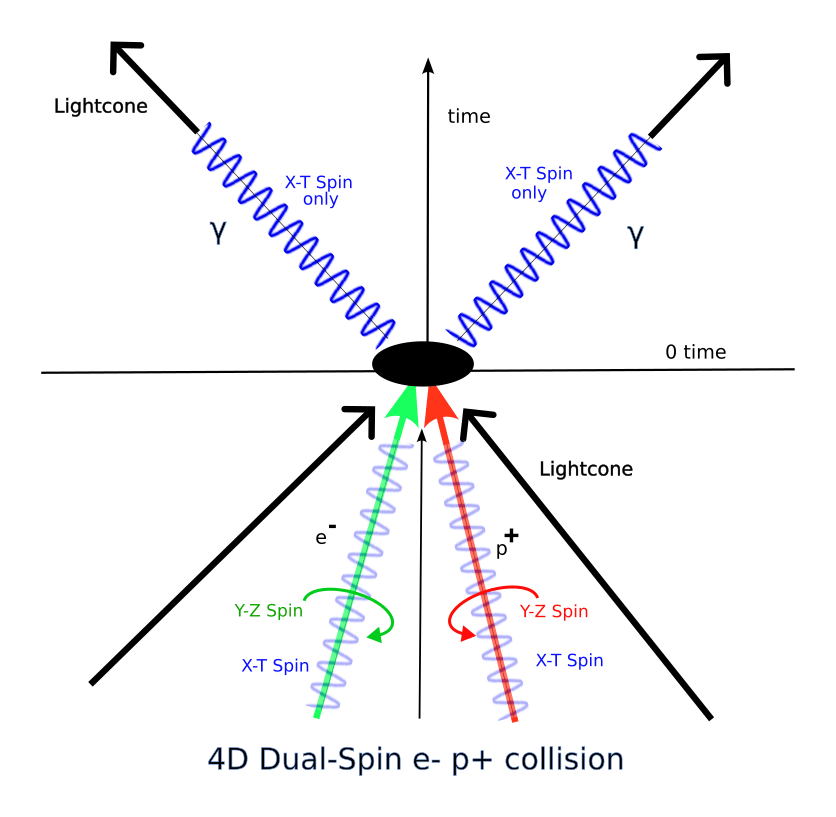

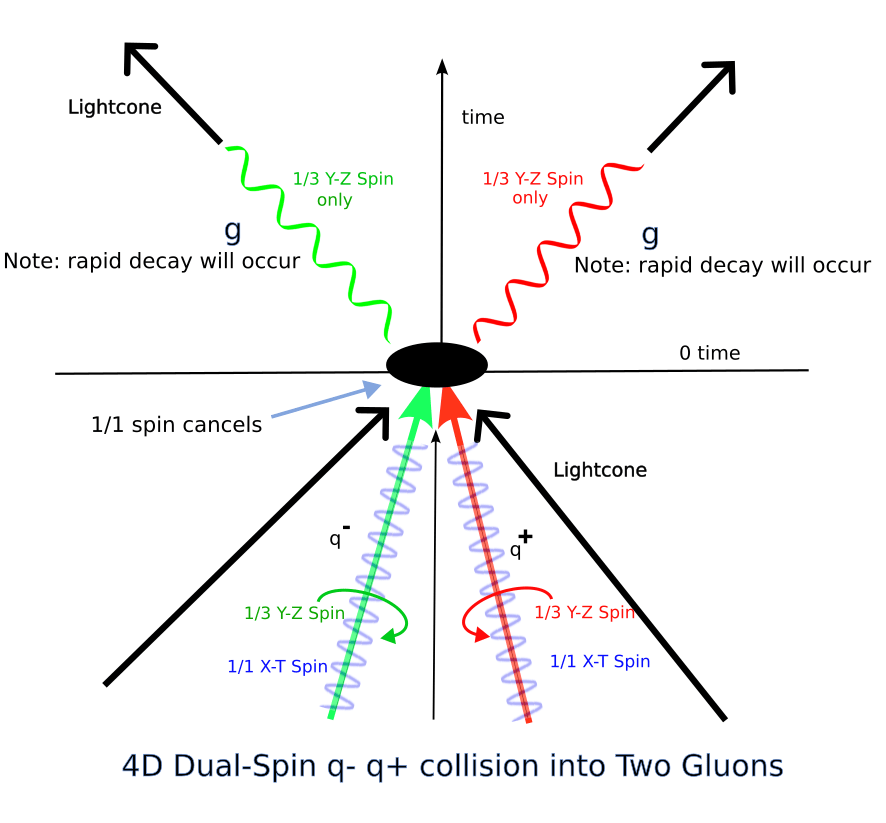

One of the principle properties resulting from an emergent field is the embedding of the particle definition within the field as a group composition of waves rather than the standard model way of assuming particles among fields. In my last post (https://wordpress.com/post/agemozphysics.com/1860) I gave an example of a spin twist in a vector field that has rotations quantized to a lowest energy background direction such as toward the time dimension. In this light, when you look at quantum field theories, a lot of really interesting ideas pop out–I think the most important is that separating out particles (virtual or real) from fields is a mistake. Yes, you can calculate with incredible accuracy this way, but it is a big hurdle to really understanding what is going on.

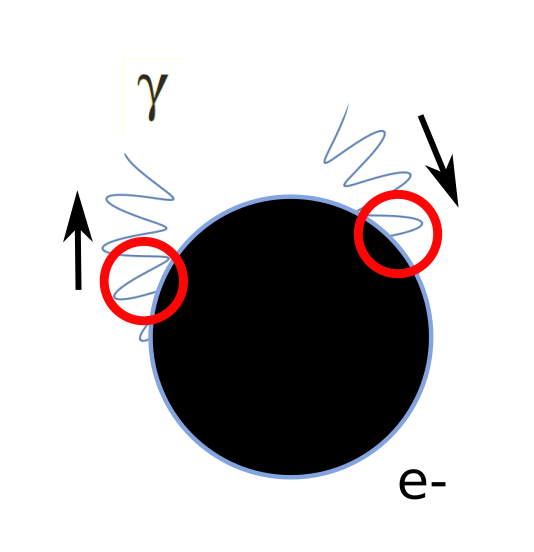

Let’s look at the very simplest quantum field case, the electron emitting and absorbing a virtual photon, one of the components of the electron’s self energy that resists its motion.

In the standard model, we compute electron equations of motion (LaGrangian minimum energy paths for the electron’s probability distribution) by assuming a random emission of a virtual photon particle, and then add in the contribution due to its re-absorption. There is an electron momentum change at emission and re-absorption, and all the possibilities of when and where and how much effect are all summed in as probability amplitudes. Not surprisingly, we can get infinite values in some cases, so we sum everything up anyway, cancel out what infinities we can, and then renormalize the probability distribution to get back finite answers (I’m glossing over a lot of the complexity of this, but that’s the idea). We also have to add in the smaller possibility of electron/positron pair formation, even the possibility of quark/gluon formation for whatever level of accuracy we are aiming for. This perturbative approach to particle interaction computations is extremely effective and works for both leptons and quarks, but this way of thinking where we separate out the field and particle aspects of such systems shuts down any further thinking about the underlying analytic form of quantum field theories.

If we imagine an emergent field like the dual-spin method I described earlier, things look very different and appear to lead to a more precise way of understanding quantum field effects. In the emergent field approach, there are only waves, no mysterious random appearance of particles. Note that in the electron self energy case shown above, the only time there is an effect on the electron’s momentum is at emission and re-absorption.

The rest of the time, we can assume the virtual particle doesn’t exist, which means that quantum field effects can be entirely described as momentum change pairs of equal magnitude. In the standard model, this doesn’t help you, you might as well call the whole path a virtual photon particle. That’s all she wrote. We don’t currently have a picture in the standard model and current quantum field theories of what is happening at the virtual particle level, we just know the math comes out.

In the emergent field methodology, these points are “spin-off”waves from the electron wave construct. These waves will interfere with the group wave electron construct, and cause a momentum change. Just like the sum of particle paths in the standard model, you can sum all of the potential momentum changes, but something different happens if the electron is moving. Since the emergent field approach now treats the quantum field effect as waves rather than particles, the doppler shift effect comes into play along the direction of electron motion. Emissions still occur in all directions and will have identical effects on the electron (resulting in a net zero effect on its momentum), but the resulting re-absorption momentums will be different depending on direction because now we are dealing with waves that doppler shift. There will be no net effect normal to the direction of electron travel, but forward re-absorptions will be stronger and reverse re-absorptions will be weaker due to doppler shifting, and the electron will slow down. The quantum field behavior will have a net effect on the electron’s momentum, and we don’t need virtual particles to describe it.

There is a lot more to come. Let’s see if this holds up.

Agemoz