Quantum Electrodynamics and Quantum Chromodynamics invoke perturbative methods to evaluate LaGrangian motion calculations. I have a vision that a new mathematical object, a field with emergent behavior built in, would, at minimum, substantially enhance the range and generality of the computations we can do in these subjects, and additionally make new theoretical predictions possible.

When I was young, I explored the Taylor series and was completely captivated by its ability to approximate transcendental functions such as trigonometric, logarithmic, and exponential functions and reveal some of the properties of these transcendental functions. That memory has stuck with me and has awakened anew while studying quantum electrodynamics and quantum chromodynamics, and I wondered what analytic function is hiding behind the perturbative computations we now do in both fields with extraordinary complexity and accuracy. I have no doubt I am far from the first to ask this question, but this has led me to realize something important about our current mathematical knowledge of fields.

Sometimes some of the best breakthroughs in a subject have their basis in the discovery of new tools that aid in analysis, detection, or construction. Our ability to mathematically manipulate fields of all types, scalar, vector, spin, frequency domain, and momentum space has ascended to dizzying heights. Fields can be mathematically constrained to special relativity and even equations of motion on curved manifolds is now routine. We can even do accurate computations when all we have are fields of probability distributions.

What we don’t appear to have is a type of field that has the creation/annihilation operators built in, and it reminds me so much of the thought processes I went through in my exploration of the Taylor series so many years ago. Since then I have learned that most series do not have an analytic representation, and many properties cannot be determined from the series representation–so it is not given that there exists an analytic solution to the summing of Feynman paths we now do for quantum field theories. Nevertheless, I have spent some time thinking how we might come up with an object called an emergent field, and what kinds of mathematical methods could be derived for it.

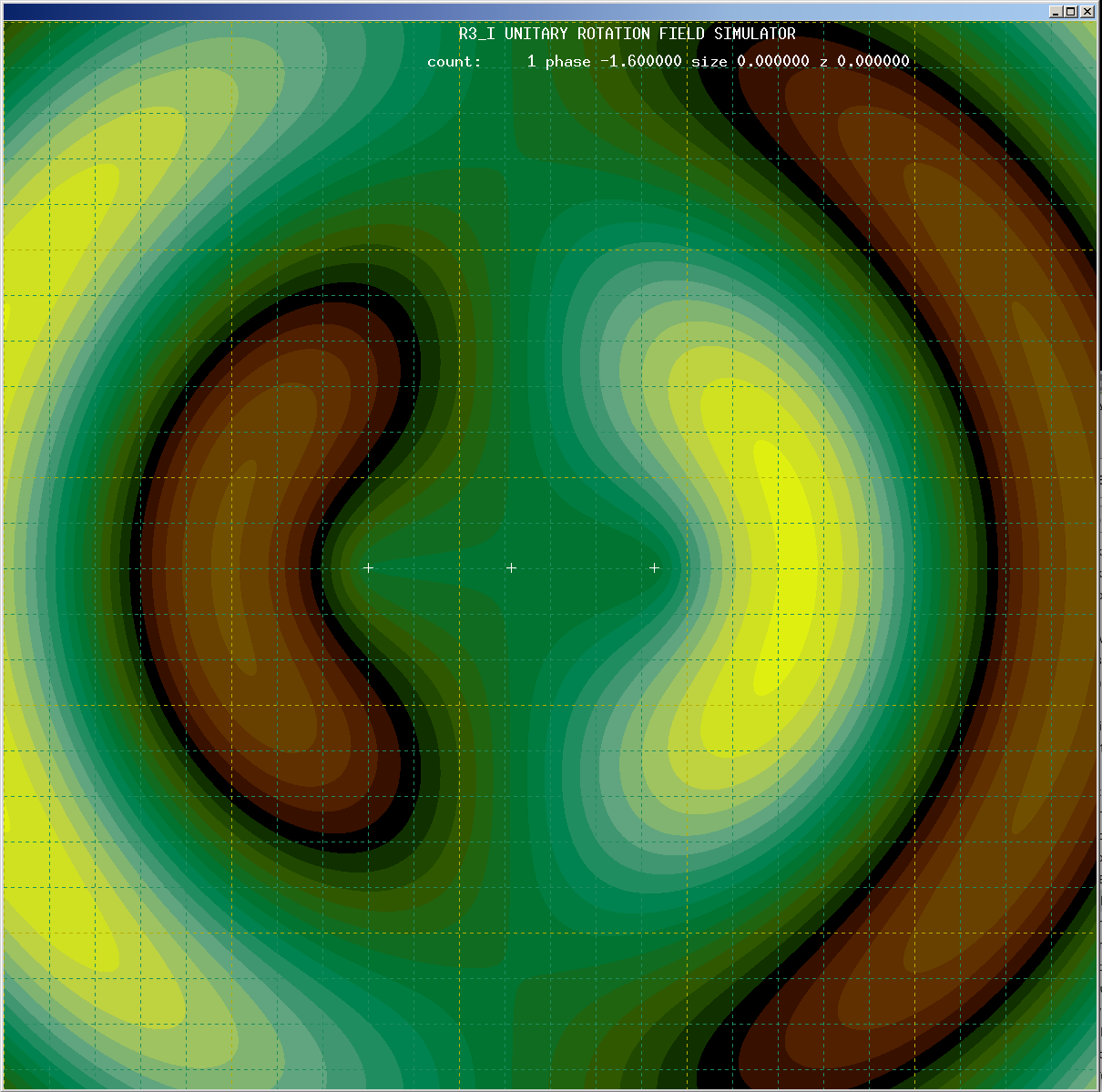

The first step in constructing a new mathematical tool has to begin simple just to see if something sticks. Like the list of integrals with analytic solutions, we may end up with a very small list compared to the overall infinite number of integrable functions. So, I started with a couple of principles that should limit the complexity of an emergent field type. There is no reason why we have to start in 4D spacetime, we can develop principles from a 2D space or even a 1D space with a 2D spin rotation, and see if a LaGrangian equation of motion can be computed that intrinsically has the creation and annihilation operators built in. Since an emergent particle can appear randomly at any time and place, I am proposing we work in a probability space with wave functions rather than physical representations. Another important principle is that the field must consist entirely of waves, and that any localized particle that forms in this field must decompose into a group wave. I did a lot of work a bunch of years ago that showed that such a system will always obey special relativity (see this paper: https://agemozphysics.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/group_wave_constant_speed.pdf). It uses a Green’s function type of derivation to show that any classical system of group waves will obey the constant speed property of special relativity.

There are other constraints that could be added–for example, you can quantize particles into stable solitons if you do something like the dual-spin particles I have spent a lot of time with (see https://wordpress.com/post/agemozphysics.com/1820 and https://wordpress.com/post/agemozphysics.com/1839). It turns out this, or something like this, is required if you want to successfully create an emergent field object.

How is this new field object going to be different than what we now do in existing quantum field theories? First and foremost, we can’t think in terms of sums of virtual particle contributions or we will be right back where we started with perturbative theory. It has become clear that the field is going to have to have a more general representation of both particles and virtual particles, and thus this field object cannot have particles in it (I already know that from the constant speed research I mentioned above). The particle definition we get in quantum field theories has to come from the field itself. I believe one good candidate is a spin rotation with a lowest energy background state (pointing in the time direction, to use the 4D dual-spin particle as an example). Here we can represent real particles as a complete quantized rotation, but virtual particles would be partial rotations that fall back due to not having sufficient rotation energy to complete the twist past the background state. All we need now is a mathematical description of the probabilities that such spins, either virtual or real, will emerge. I think you can see where I am going with this, and I’ll share more of my thought process and analysis in upcoming posts.

It is my vision that someday soon some really brilliant mathematician is going to come along and finally create an emergent field object, and he or she will develop a full set of rules how this object behaves. I’m obviously not that mathematician, but I do clearly see that future coming…

Agemoz