I set up a quantum interference unitary rotation vector field sim with a very basic idealized representation of a two pole “electron” and a much lower frequency one pole “photon” along the z-axis, and here is what I found:

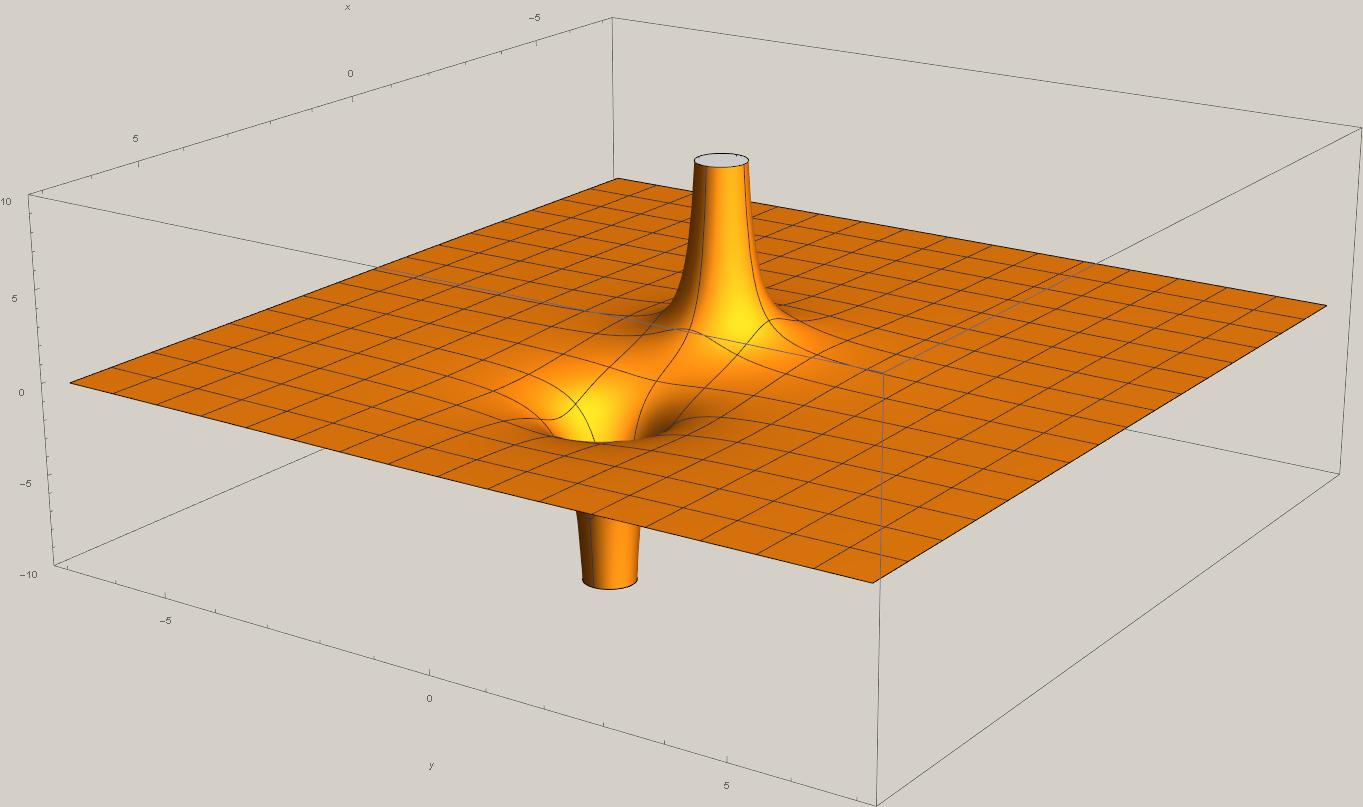

a: The “photon” wave (photon meaning the sim model of a photon in this post) makes the two pole electron unstable at the z = 0 axis position. Instead, the stability region moves along the z-axis depending on the phase of the photon pole. As a result, the quantum interference pattern from all three poles appears to force the electron to translationally move along the axis of the photon z displacement, which matches the expected electron-photon interaction behavior.

b: Depending on the phase of the incoming one-pole photon, I found that the stability region for the two-pole electron can either be below (away from) OR above (toward the photon). Could we at last have an explanation for why electrostatic fields emitted from a source can either repel or attract?

There is a momentum paradox in electrodynamics–if photons have momentum toward an electron, how can momentum be conserved if the electron ends up (due to charge attraction) with momentum in the opposite direction (toward the photon)? Quantum field theory computes that the field itself absorbs the momentum difference (and yes, mathematically that works) but intuitively I rebel at that analysis. The unitary rotation vector field appears to be providing a very elegant solution–quantum interference directs where the electron stability region has to go via wave interference, and in some phase cases it exists toward the photon rather than away from it.

c: It doesn’t matter where you put the photon. I get the same results regardless of the photon offset in the x-y plane (although as mentioned, the z offset causes the electron stability region to move along the z axis).

d: It doesn’t matter what frequency is used for the photon, although the stability region displacement above or below the electron initial position will vary linearly as 1/photon frequency. Higher frequencies cause the photon phase change and hence the change in z displacement to occur at a faster rate, lending credence to the idea that higher momentum photons will induce a larger momentum change in the electron.

e: The only thing the sim seems to get wrong is the absorption of the photon, which should disappear after encountering the two-pole electron. This will require more investigation.

So, in summary, at least on this first pass of testing, the hypothesis that quantum interference in a unitary rotation vector field is responsible for particle formation and particle interactions appears to behave correctly for the electron/photon interaction test.

That by no means is saying that my hypothesized unitary rotation vector field represents reality (if a real physicist were reading about my efforts, he/she probably would wish my efforts would die in a fire if I said something like that) but it looks pretty promising right now. In time and with more work, who knows where this will go–but the real test will be for some qualified researcher to confirm what I am seeing. Until that happens, you should assume that this is unreviewed work (by one author, the kiss-of-death for a research paper) and take it with a bucket of salt…

Agemoz

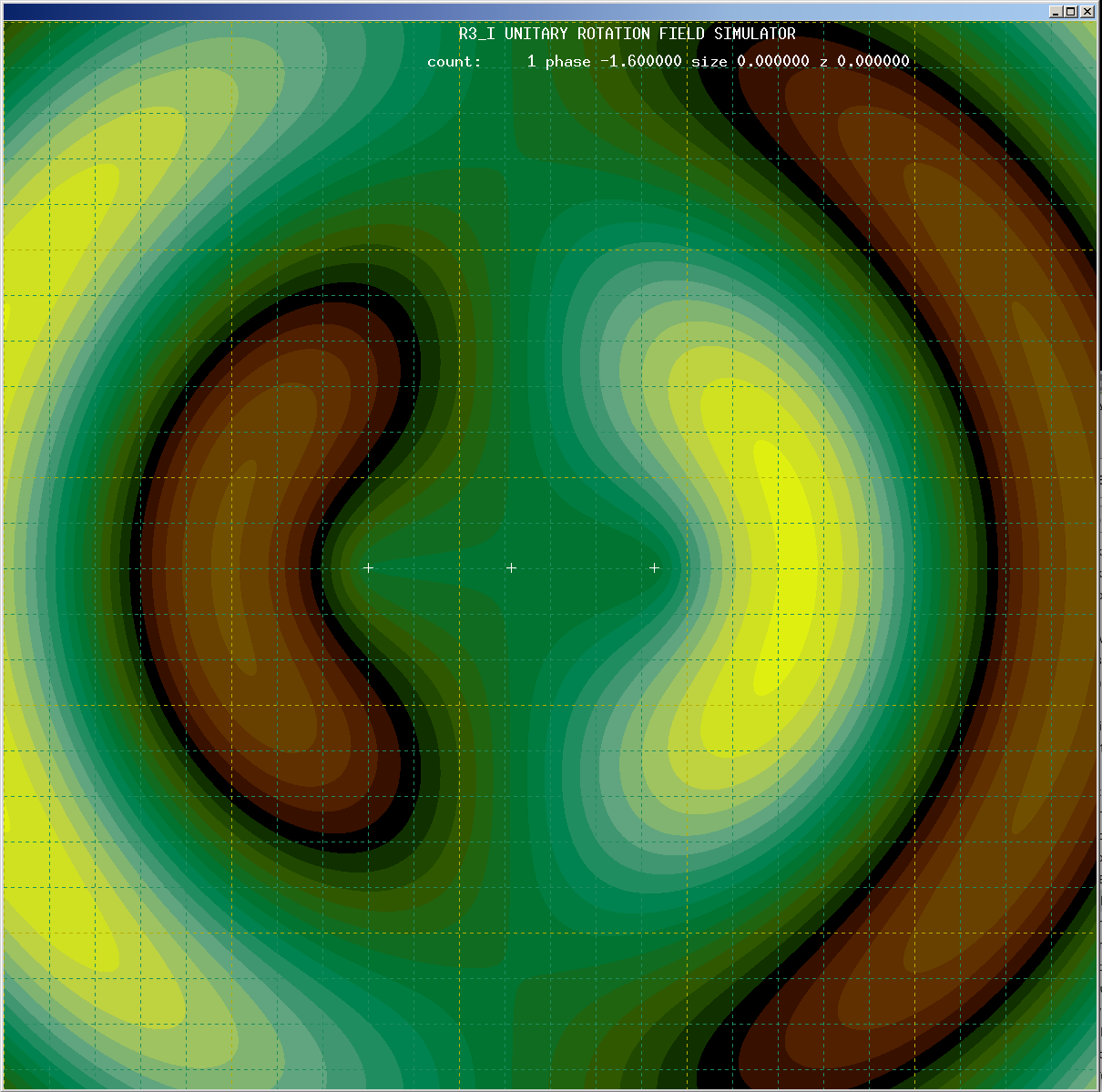

Here is a picture with the photon in the center, and the z plane is at zero (note this picture cannot be stable, the outside crosses are not in zero delta phase regions)

Looking at the same image, the region of stability has relocated closer to the photon (representing electrostatic attraction).

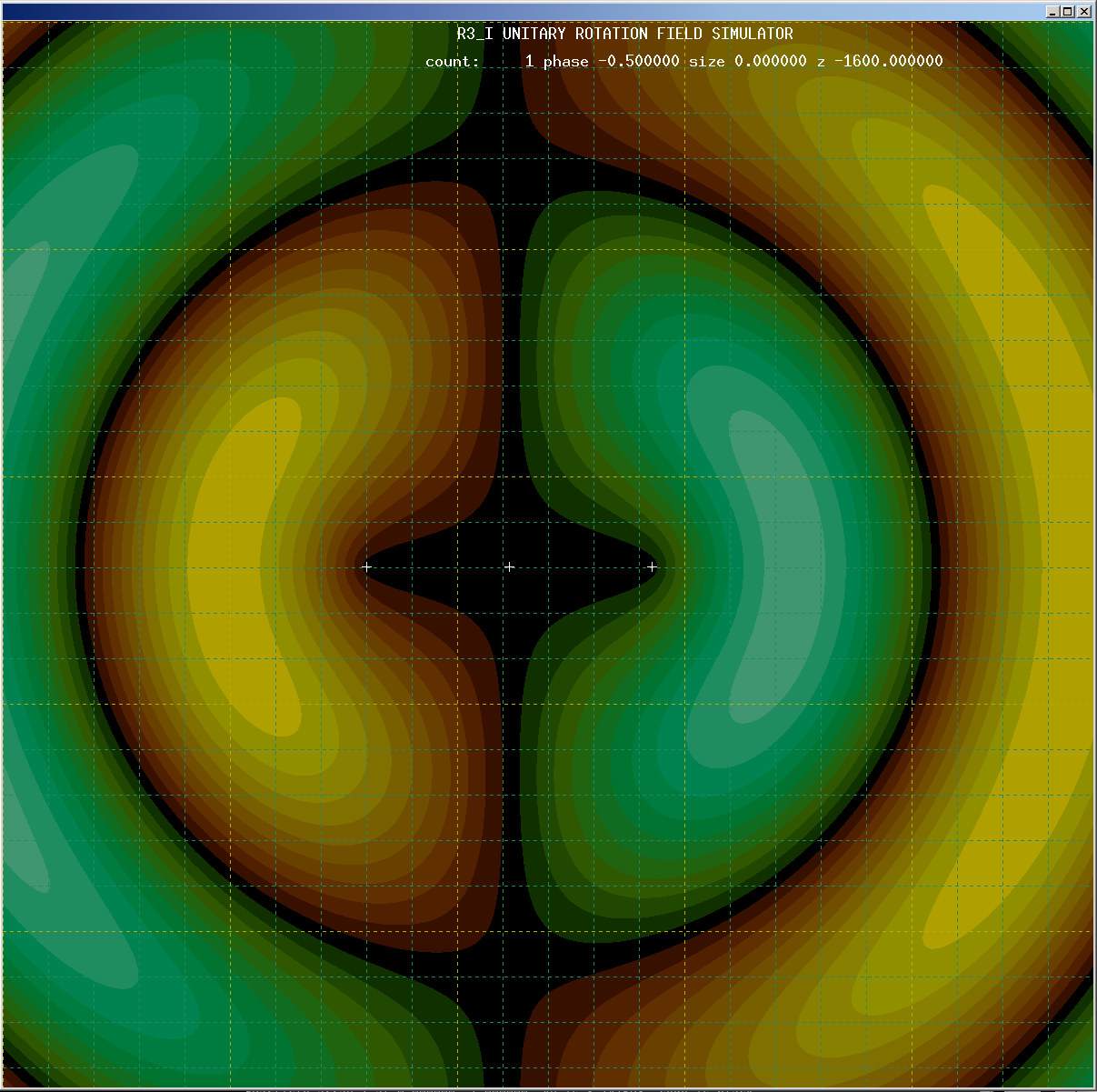

The region of stability displacement linearly varies as the phase shift induced by the photon, notice the region for a smaller phase shift has not relocated as far from the original electron position:

Agemoz

Agemoz

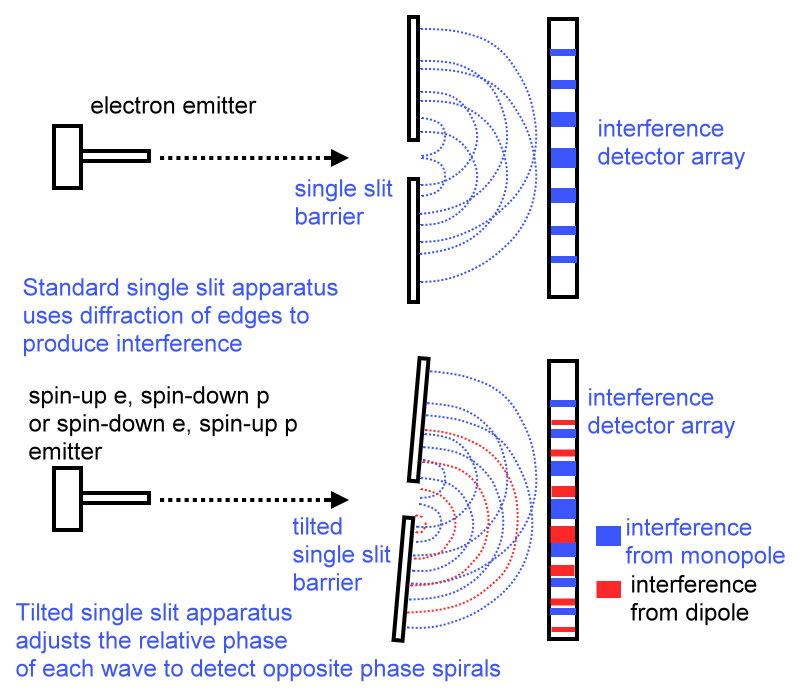

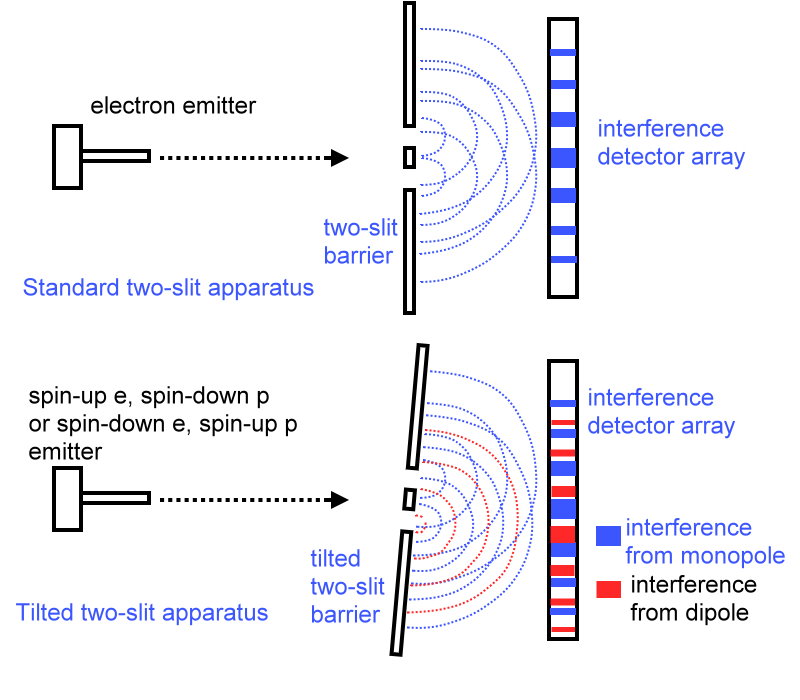

If you get two distinct interference patterns, one for each pair, the conclusion is unmistakable–the particles have a spiral wave pattern and form from a dipole. If the pattern is the same for all particles, they have concentric circle wave patterns and form from an oscillating or twisting monopole.

If you get two distinct interference patterns, one for each pair, the conclusion is unmistakable–the particles have a spiral wave pattern and form from a dipole. If the pattern is the same for all particles, they have concentric circle wave patterns and form from an oscillating or twisting monopole.