We have substantial experimental evidence that elementary particles such as the electron and quarks are point particles. From a idealized geometric point of view, point particles in three dimensional space are relatively uninteresting with only one possible spin axis and no internal structure. However, we also have significant experimental evidence of four dimensions including curvature in the time dimension, so it is very reasonable to assume that spin angles can point in that direction. In fact, point particles in four dimensions can have two independent spin planes, one in the X-T plane and one in the Y-Z plane, for example. A simple thought experiment that proves this possibility: You can imagine a top spinning in the Y-Z plane and then rotate yourself as an observer through the X-T plane. This proof works identically for quantum spin wave functions, so no objection there–and since there is no physical or timewise displacement, dual-spin point particles will not violate any aspect of special relativity. There is clearly nothing in this geometry that prevents this from happening in reality, so I recall the comment from the Interstellar movie that Murphy’s Law posits that “anything that can happen, will happen”. In my opinion, I think that point particles in four dimensions would mostly likely form with spins in both of the independent spin planes–setting one of the spin rotations to a constant seems really improbably in a relativistic universe.

Dual-spin point particles are particularly interesting to think about in context of creation and annihilation of elementary particles. Examining the details of the electron-positron annihilation exercise, assuming dual-spin particles, looks like this:

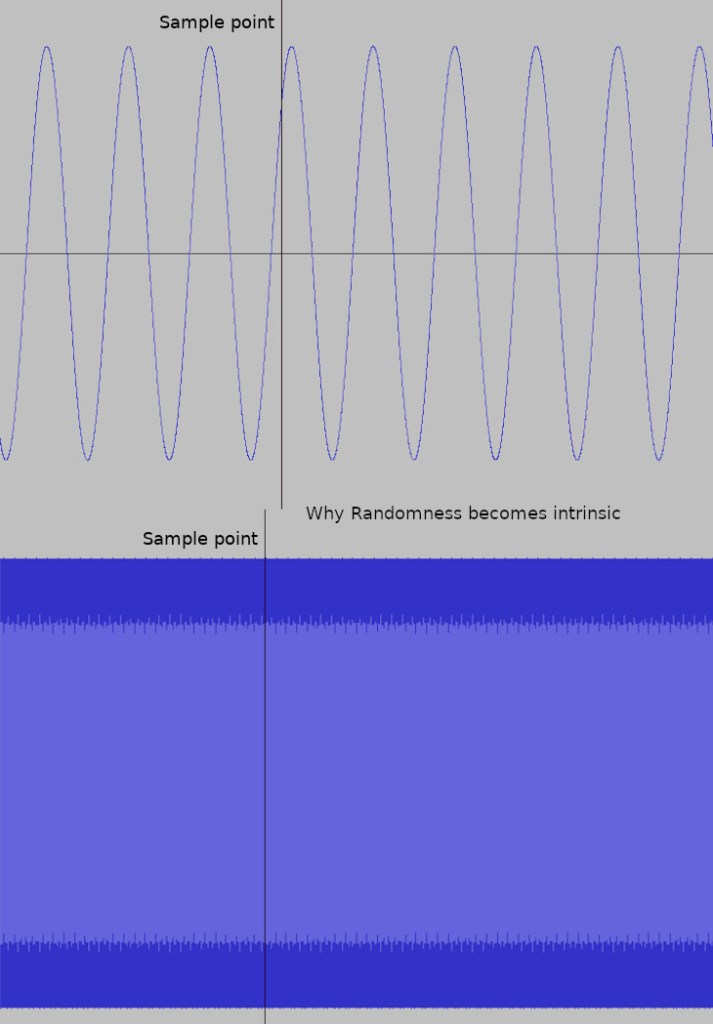

Before the collision, there are two massive particles with charge, and after the collision, there are two particles with no rest mass and no charge. The idealized case can be analyzed by assuming there is near zero electron/positron momentum so that all of the momentum (minus some epsilon amount) is in a momentum wave traveling in the T dimension direction. After the collision, the momentum is split between the X direction and the T direction such that the X rate of change in T equals the speed of light–it travels on a path lying on the collision point light cone.

Now, let’s do an ansatz that the point particles are dual-spin point particles and see where that goes. Let’s assume that the X-T spin sets the momentum of the point particles both before and after the collision. Now assume that the Y-Z rotation only exists before the collision–the annihilation cancels out this spin because the anti-particle positron has the opposite Y-Z spin of the electron. We can then see that the X wave displacement after the collision cannot coexist with the Y-Z rotation before the collision. The 4-momentum of the photons must equal the sum of the 4-momentum of the particles and the angular momentum of the massive part of the electron and positron prior to the collision. The collision is the cause of an exchange of all of the Y-Z spin to all of the X displacement of the transformed point particles, you cannot have a mixture of both.

This thinking gives me several insights. The X displacement of the resulting photons is fixed at the speed of light, so this must quantize the possible Y-Z spin–thus giving an explanation why we get a single possible mass of the electron or other elementary particles, depending on the dual spin ratio (see previous posts such as agemozphysics.com/2023/12/28/the-higgs-field-and-r3t-dual-spin-point-particles/). As the universe cooled from the Big Bang, this quantization gives us a phase transition, a symmetry breaking, at the energy wavelength of electrons or quarks. It also hints at why photons have no rest mass and must move at the speed of light. It also suggests that inertial mass and charge result from the Y-Z rotation, which disappears after the annihilation.

Does this fit with the Standard Model, such as the how it derives the Higgs particle interation or the strong force interactions between quarks and nucleons? Does it show why the phase transition point for protons is 1836 times the energy of electrons? Well, no–if it did I would have an actual discovery to report… !

Agemoz