Charged point particles are very interesting because there’s only a few ways to produce stable (static) configurations of them. You cannot create a 2 particle solution or 6 or more particle solutions. Only three solutions exist: an in-line 3 particle solution, a 4 particle solution, and two 5 particle solutions (see the last few previous posts).

UPDATE: I have found that these charge stable particle solutions fall into a single class of solutions with one or two center particles, where the remaining particles have opposite charge and are equally spaced on a sphere about the center particle(s). If there are two center particles, they have to lie equally spaced on a line normal to the plane of a circle on the sphere (therefore, the three particle solution cannot have two center particles since three particles define a plane). I’m continuing to see if there are any other stable solutions, but after quite a bit of thinking, I see no more. The set of stably charged solutions is really small–there is only this class of solutions and no others–and it does appear to have a curious, possibly interesting, mapping to quark combinations as mentioned in the rest of this post.

Continuation of the original post:

This gets really interesting when applied to electrons and quarks. If you do a little “quark algebra” like this (I’m ignoring the relatively tiny neutrino component):

proton = u + u + d

neutron = u + d + d, which decomposes to a proton, e-, and neutrino -> u + u + d+ e- + O(0)

this leads to

d = u + e-

which then gives

proton = u + u + u + e-

neutron = u + u + u + e- + e-

These match two of the available stable charged point particle configurations, so I got very interested in studying this construction–seems like there might be a path to some kind of truth here. However, computing the traditional inter-particle forces q1q2/r^2 gives the required charge for the up quark that is not 2/3, but sqrt(3) electron charge.

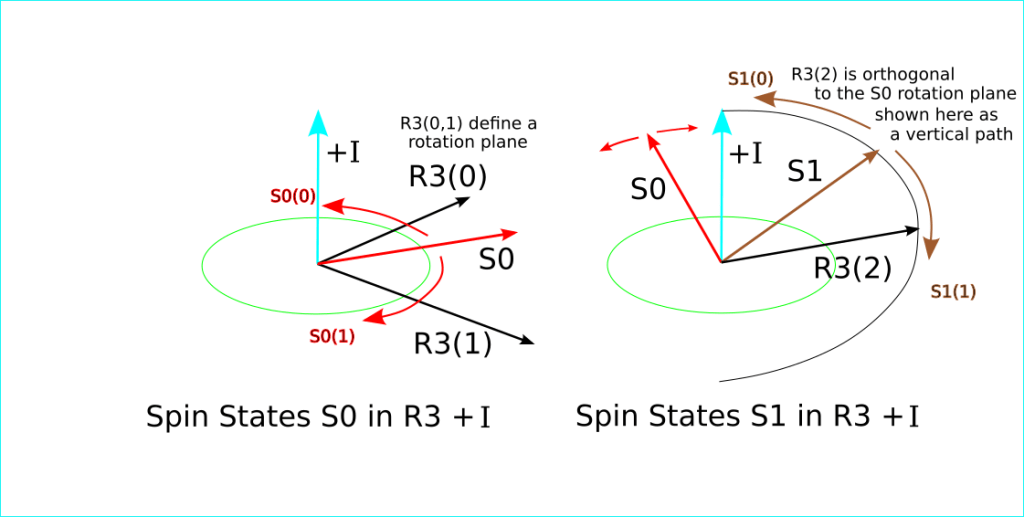

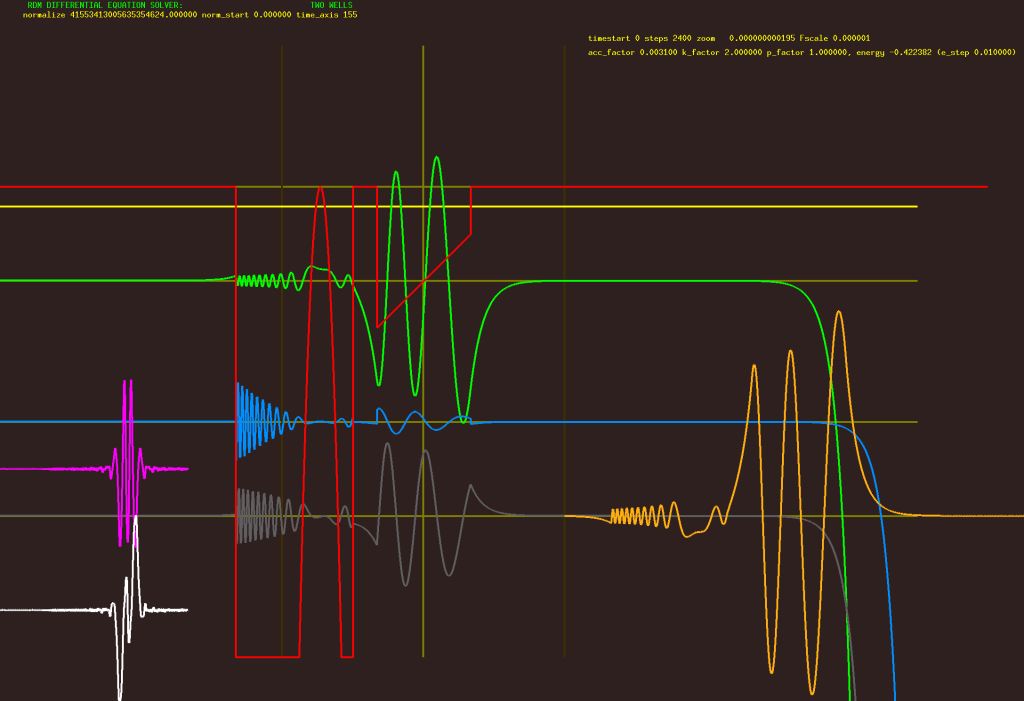

I studied this for a while to see if my Schroedinger wave solver would give some insight, but it didn’t. It did show that one solution is to add a momentum term to Psi for the up quark (implying an orbital), but this did not get anything close to the expected up quark charge.

This problem (getting the correct value for the forces involved) is analogous to the quantum field issues encountered in the electron-photon interaction, and thus is likely to be a hard problem to solve. For example, I am assuming a shielded electron charge, ignoring creation-annihilator effects, ignoring vacuum polarization, ignoring well-researched strong force implications, etc, etc.

Nevertheless, I continued my thought process–I looked in detail at the development of the electron-photon interaction in quantum field theory. It establishes that charged attraction/repulsion is mediated by quantized photons, either virtual or real. On the macroscopic scale we model attraction with a central force (1/r^2) electrostatic field. At the quantum scale, I think there is evidence that something different happens.

I see a very important key with this discovery: any linear force granular particle interaction will always obey the central force property for far-field interactions simply because there is a 1/r^2 diminishing number of particles per square area as you move away from the source emitter. The particle current density in expanding spherical shell surfaces drops as 1/r^2.

This leads to a really important corollary: Individual quantized point particles cannot interact with a central force behavior but must interact linearly with r, otherwise the overall granular central force behavior would produce a composite function that is no longer central force.

This is why I hold the belief that quantum field renormalization is an unnecessary correction for the infinities resulting from central force (1/r^2) functions in quantum field equations as distances approach zero. Renormalization (for example, setting an r threshold or subtraction of infinities to make solutions workable) should not be necessary if we understand that electrostatic forces have a far-field central force behavior (1/r^2 dependence), but in the near-field quantized case must have a linear interaction behavior.

This near-field linear behavior also substantiates my view that the electrostatic central force equation q1q2/r^2 is not the right formula for the stable 4 point particle configuration, they must interact as q1q2/r. With this correction, we now get closer to the required 2/3 charge for the up quarks.

Fe–u = 2/3 * 1 * sqrt(3) = 2 / sqrt(3).

Fu–u = 2/3 * 2/3 * 1 * 2 * sqrt(3) / 2 = 4/3 / sqrt(3))

Now the classical intra-proton quark forces, which must sum to zero if the up quark charge is 2/3, is off by an extra factor of 2/3. I have a number of approaches underway to address this.

One hint comes from unit analysis of the coulomb unit of charge.

Coulomb(SI units) = m/s sqrt(m) sqrt(kg)

There is no physical meaning to a square root of distance (or mass, for that matter) which says to me that charge only has meaning in context with another charge. I did some work a couple of years ago that suggests that near field charges emit and absorb exchange photons that results in a linear force due to point-particle wave interference: see this post

https://wordpress.com/post/agemozphysics.com/1295

I’m going to investigate using this approach on the 4 point-particle proton and see if I get insight as to how charge would work and if I get a correct up quark value in this near-field context.

Agemoz

PS: It is very interesting to me to think about gravity in context with the above-mentioned granular-particle rule and the corresponding central force corollary I discuss. Gravity is, of course, another central-force interaction–but to the best of our knowledge and observations, unlike quantum particles, there is no evidence of linear gravitational behavior at any scale, massive or tiny. I think this may be evidence that gravity is not quantized.