UPDATE: it turns out, due to a ColorFunction bug in Mathematica, my conclusion from the previous post is incorrect, and the idea of using dual-spin particles in R3+T may not work as a simple model for bound quarks–see the addendum below.

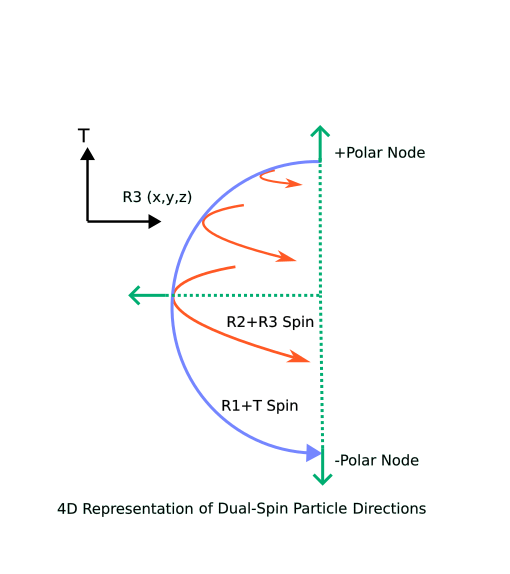

ORIGINAL POST:Our existence lies in a three dimensional slice of spacetime called a hypersurface that I have chosen to call the “activation layer”, since interactions, whether quantum or relativistic, can only happen here. I have discovered that point particles in R3+T spacetime can have two simultaneous spin axes, for example one in the R1-R2 plane and one in the R3+T plane. This is different than spins in 2 or 3 dimensions, which can only spin on one axis.

I’ve recently created a number of posts on this blog detailing some of the basic properties of “dual-spin” particles, and showed how such particles form a hypothetical foundation for why we have the real-life particle zoo of our existence. The fact that electrons form a class of four identical mass and charge particles (spin-up, spin-down, and their antiparticles) falls nicely out of the dual-spin concept, and recently I found that some ratios of the dual spins turn a single point particle in R3+T into two or three distinct particles in R3 (see https://wordpress.com/post/agemozphysics.com/1754). It is easy to think that this is why we see bound quarks–in R3+T–it is a single particle and cannot break apart.

I think there is a lot going for this idea, but it makes me really nervous to postulate a concept that is so distant from the known and verified quantum field theory and the standard model we now use. For example, in the dual-spin concept, where are the gluons? How do you get the very high ratio of proton mass to electron mass if both are single point particles (with different dual-spin ratios)? How do we describe the strong force in a dual-spin system? What is the difference between a proton and a neutron when built from dual-spin particles? What stabilizes the neutron when in the presence of a proton? What are neutrinos and muons? What explains the parity violation? When an idea like the dual-spin point particle is this far removed from known science, there is just a ton of work thinking about all the connections that have to be established, before even thinking about any new science. And without new science, I am just spitting in the wind.

So, I take each aspect one at a time, and first look to see if there is a fit or if the model simply won’t work no matter what.

It was a major revelation to discover that the dual-spin point particle creates the illusion of three particles in our activation layer hypersurface. The projection onto R3, the only place where interactions can occur, creates some unexpected consequences that do seem to point to a match to reality. I then realized that this revelation has a really important corollary in how the point particle will respond to acceleration. In other words, different dual-spin ratios have to have a significant impact on the apparent mass of the R3 activation layer pseudo particles.

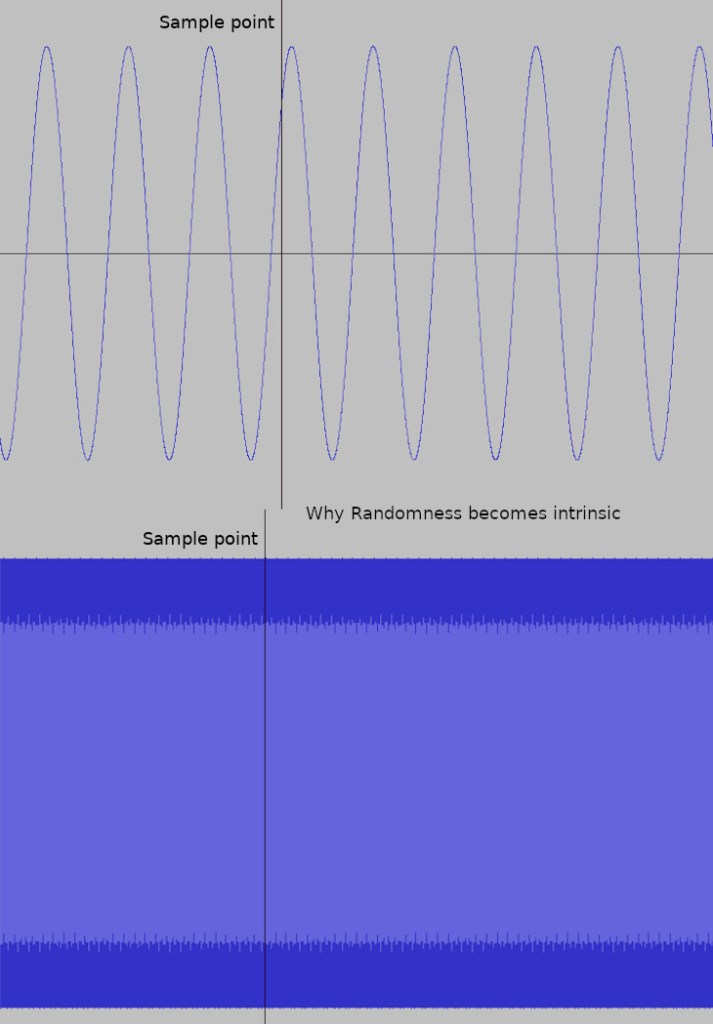

There are two ways to increase the mass of a particle. The obvious one is to increase the rest mass by adding mass to it–attaching more particles, connecting to a field via bosons, and so on. But there is another way that is enabled by the four dimensional nature of dual-spin point particles. If an inertial force is accelerating a particle that constantly pops in and out of the activation layer, the force only gets a fraction of the time to accelerate the particle. The effect is exactly identical to if the particle has proportionately more mass, and in the case of the dual-spin representation of quarks, I see several ways we could get the expected mass ratios to the electron (.511Mev electrons to 2.2Mev up quarks and 4.8MeV down quarks). Yes, that is numerology, a no-no in physics, but the procedure is definitely mathematically sound. The big question is whether this represents reality, and for that, I have to continue this study.

UPDATE 12/6/2023: The various dual spin ratio cases do indeed have some instances where a single R3+T particle become visible to us as two or three particles in R3 due to the activation layer hypersurface we live in, but they are all identical in mass. There is a bug in Mathematica where the ColorFunction method does not correctly track in a parametric3D plot, which caused me to observe an incorrect property for one of the three particles in R3. I found a workaround in Mathematica that correctly shows three identically spaced particles where the observed mass in R3 will all be identical. Unfortunately that won’t work as a model for the quarks in a proton. So, I have to back up a few steps in this hypothesis. Maybe the dual-spin idea will still work in some way, but it’s not there yet. I now have categorized all of the bound particle combinations that result from dual-spin particle ratios. While dual-spin particles are an interesting mathematical concept, I’m no longer seeing a clear path to the particle structures we have in real life.

Agemoz