I’m going to do something a little different in this post. It’s every amateur’s dream to be taken seriously by the professionals, so I’m going to have a little fun today and pretend that a physics professor looked at this and decided to be nice (he just got a big grant approved for his research and was feeling unusually magnanimous) and go over it with me. This is not for real–a real professor would almost certainly not give the time of day to an amateur’s ideas–it just is too much work to dig in and be precise about why any set of ideas wont work, nevermind those from someone who hasn’t spent a lifetime dedicated to this field of study. But, amateurs all get their Walter Mitty dreams, and this is mine–and this is my blog, so I can do what I durn please here! Actually I don’t care if I’m recognized for anything I come up with, but it’d be cool if some part of it turned out to be right. Anyway, here goes.

Prof Jones: Hello, what do you have for me?

Me: I have this set of ideas about how particles form from a field.

Prof Jones: You have a theory [suppresses noisy internal bout of indigestion]

Me: Well, yes. I think there is a geometrical basis for quantum and special relativistic behavior of particles.

Prof Jones: We already have that in QFT. Are you adding or revising existing knowledge? I’m really not interested in someone telling me Einstein or anybody else was wrong…

Me: I believe I am adding. I have tried to take a overall high-level view of what is now known, especially the E=hv relation and the special relativity Lorentz transforms, and see some conclusions that make sense to me

Prof Jones: Well, I’ve had a lot of ideas thrown at me, and they are a dime-a-dozen. It’s not the idea that’s important but the logic or experiment that supports it. A good theory explains something we don’t understand and allows us to successfully predict new things we otherwise would not find. Is yours a good theory? Do you have supporting evidence or experiment? Can you predict something I don’t already know with QFT? Does it contradict anything I already know? If you can’t pass this complete criteria, the theory isn’t going anywhere but the round file.

Me: I don’t have anything that proves it. I don’t have anything it predicts right now but I see some possibilities. I don’t think it contradicts anything, but there are some question marks.

Prof Jones: Urrg…. Well, this is your lucky day. I happen to be in the mood for shooting down the bright ideas of poor suckers that think Nobel prizes are given out like puppies from a puppy mill to people that haven’t paid their dues in this very, very tough field. So, let’s start with this question: What makes you think you are the one that has come up with something new in quantum theory? After all, you can’t argue that the set of smart-enough people that actually can legitimately call themselves physicists, theoretical or related, have spent cumulative millions of lifetimes trying to break down the data and clues we have to solve the very well-known problem you are looking at. Don’t you think someone, or many someones, with a much deeper background than you would have long since considered whatever you have and passed it by fairly quickly?

Me: [meekly] yes.

Me: But I have thought about this for a very long time, and refined it, and received feedback, and really tried hard to make sure it makes sense.

Prof Jones: Unfortunately, so has every honest physics PhD, and I’m afraid they are going to have a lot more mental “hardware” than you, having both genuine talent and also having brutally difficult training in abstract mental comprehension and synthesis ability and current knowledge.

Me: OK. I guess I could quit doing this–I just find it so interesting.

Prof Jones: [softens just slightly, realizing there’s a lot of snarky but not-classy power in putting down those who try, but are so limited in resources or study time]. Well, just so you understand. You aren’t going anywhere with this. But let’s see what you got. Before I dig in, I want to know what you are adding to existing theory, as succinctly as you can communicate.

Me: Alright. I thought about the way quantization works on particles and fields, and in both cases the E=hv relation defines very explicitly what must happen. I spent a lot of time trying to construct a model of a system that is continuous but obeys this relation at the smallest scale. I came up with three constraints that describe such a system–in fact, it looks to me that the E=hv relation actually specifies a geometrically defined system. These constraints are:

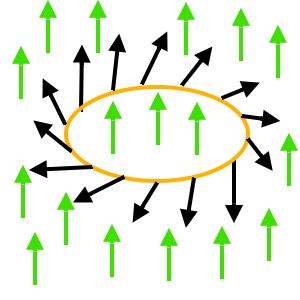

1: The quantization is enforced by a rotation in a vector field, that is, a twist.

2: To ensure that only single complete rotations can occur, the field must have a local background state that the rotation returns to.

3: To ensure that the energy of the rotation cannot dissipate, the vector field must be unitary. Every field element must have constant magnitude but can rotate in 3D+T spacetime.

Prof Jones: I see what you are getting at. The E=hv relation only allows discrete energy states for a given frequency within an available continuous energy range. A twist is a modulus operation that works in a continuous 3D field to provide such discrete states provided that there is a default idle state, which would be your background vector orientation. However, you realize that EM fields do not have limitations on magnitude, nor is there any evidence of a background state.

Me: I understand that. I am proposing that because QFT shows how EM fields can be derived from quantum particles (photons), my theory would underlie EM fields. I see a path where EM fields can be constructed from this Unitary Twist Field Theory from sets of quantized twists. I agree that the background vector direction is a danger because it implies an asymmetry that could prevent gauge invariance–but I suspect that any detector built of particles that are formed from this twist mechanism cannot detect the background state. The background state direction doesn’t have to be absolute, it can vary, and a unitary vector field has to point somewhere. Continuity and energy conservation imply that local neighborhoods would point in the same direction.

Prof Jones: Sets of quantized twists, hunh. Well, you’ve got a very big problem with that idea, because you cannot construct a twist in a background unitary vector field without introducing discontinuities. If you have discontinuities, you don’t have a unitary vector field.

Me: Yes, I agree. However, if the twist moves at speed c, it turns out the discontinuities lie on the light cones of each point in the twist and are stable, each light cone path has a stable unchanging angle. In a sense, travelling at the speed of light isolates the twist elements from what would be a discontinuity in a static representation.

Prof Jones: I don’t think I agree with that, I would have to see proof. But another question comes to mind. In fact a million objections come to mind but let me ask you this. You are constructing an EM field from this unitary vector field. But just how does this single vector field construct the two degrees of freedom in an EM field, namely electrostatic fields and magnetic fields? Just how are you proposing to construct charge attraction and repulsion and magnetic field velocity effects specified by Maxwell’s relations? QFT is built on virtual particles, in the EM case, virtual photons. How are you going to make that work with your theory? You realize the magnitude, don’t you, of what you are taking on?

Me: These are questions I have spent a great deal of time with over the last 20 years. That doesn’t justify a bad theory, I know. So I’ll just present what I have, and if this dies, it dies. I’d just like to know if my thinking has any possible connection to the truth, the way things really are. I realize that we have a perfectly workable theory in QFT that has done amazingly well. But we also have a lot of particles and a lot of interactions that seem to me to have an underlying basis that QFT or relativity don’t explain, they just happen to work. Renormalization works, but why? These are some issues that tell me we can’t stop with QFT.

Prof Jones: [sotto voce] The hubris is strong in this one.

Me: What

Prof Jones: Nothing. Go on. What is your theory going to do with charge and magnetic behavior?

TO BE CONTINUED, SAME BAT-TIME, SAME BAT-CHANNEL

Agemoz